Green horizons: Skills for climate action

Romain Boitard, ETF

This article argues that climate action is an imperative rather than an option and education and labour reforms are cornerstones in the ecological metamorphosis because it needs a workforce skilled in green technologies and sustainability practices. The article describes the grave challenges of the green transition and shows that many of these are even graver in countries neighbouring the EU, but it also offers plenty of hope for these countries if they can mount a strong response. After all, they have some powerful resources, such as young populations and green energy potential.

- ✅ 1. Introduction

Governments around the world are taking action to tackle climate change while decarbonising their economies. Their success depends on how boldly they can shift to a green decarbonised economy through environmental regulations and adequately trained labour forces.

The European Union's neighbouring regions, encompassing Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Türkiye, Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, face significant and escalating vulnerability to climate change. Despite contributing minimally to past greenhouse gas emissions, these regions are increasingly grappling with the adverse effects of climate change, such as droughts in North Africa and heatwaves and floods in Europe and Asia (IPCC 2022).

Recent developments, such as the European Green Deal industrial policy, are reshaping the trade dynamics between the EU and its neighbours while the current energy crisis accelerates the transition to renewable sources and prompts the phasing out of fossil fuels (Kuzemko et al 2022).

But system changes are no longer a mere introduction of new technologies. They require a radical review of the entire framework through which societies operate and interact with the environment (Markard et al 2012). In this massive transformation process, education and training policies are central.

This paper, based in part on ETF research, explores how education, skills development and labour markets in the neighbourhood region are affected by the green transition and provides insights into the necessary system changes.

- ☀️2. Climate change in the EU neighbourhood

- ? 3. What is the green transition

Every new term evolves and resonates differently depending on its context and ‘the green transition’ is no exception. For the needs of this paper, it is defined as a fundamental shift towards sustainability and environmental stewardship that transcends national borders. It stands for the collective effort to combat climate change, reduce pollution and material use, preserve biodiversity, and promote sustainable development practices, such as the circular economy. Importantly, this transition is intricately linked to the emergence of a green economy – an economy ‘that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. It is low-carbon, resource efficient, and socially inclusive’ (UNEP, 2011).

It is critical to our definition of the green transition that it is not confined to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. It also entails a broader transformation of the way in which societies operate and interact with the natural world. It takes in sustainable practice from across various sectors, such as agriculture, mobility, manufacturing and urban development, fostering an inclusive approach to ecological and economic well-being.

Economically, this transition encourages innovation in green technologies and sustainable business models, creating new job opportunities and markets. Socially, it emphasises environmental justice, aiming to distribute the benefits and burdens of environmental policies fairly and to prevent marginalised communities from being disproportionately affected. In essence, the green transition is a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach that recognises the intrinsic link between environmental issues and broader economic and social dimensions.

From this perspective, the green transition requires rethinking and redesigning the entire framework of how societies operate and interact with the environment (Markard et al, 2012). ETF research found that the green transition is advanced by diverse key drivers, involving a combination of environmental, economic, technological and societal factors (ETF 2023a; ETF 2023c).

The ETF found that environmental concerns, such as citizen’s demonstrations and activism, incentivise decision-makers to address climate change and environmental degradation. Innovation and technological progress are essential enablers. Policy and regulatory frameworks encourage green practices, such as subsidies for energy efficiency retrofitting. Economic incentives, such as the economic viability of renewable energy sources and the potential for green jobs and growth, significantly motivate governments. Enhanced public awareness of environmental issues and consumer demand for sustainable products and practices influence businesses and governments. Global agreements like the Paris Agreement establish the framework for coordinated international action towards a green transition.

- ?4. Threats to the green transition

- ⏫5. Advancing the green transition

- ?6. Challenges to education and training

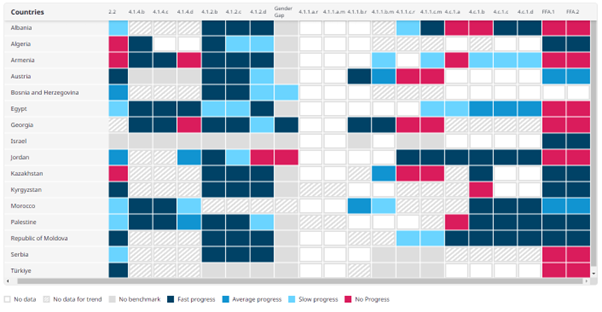

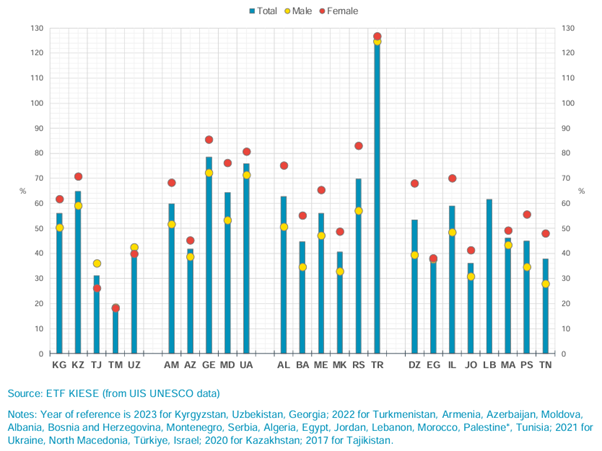

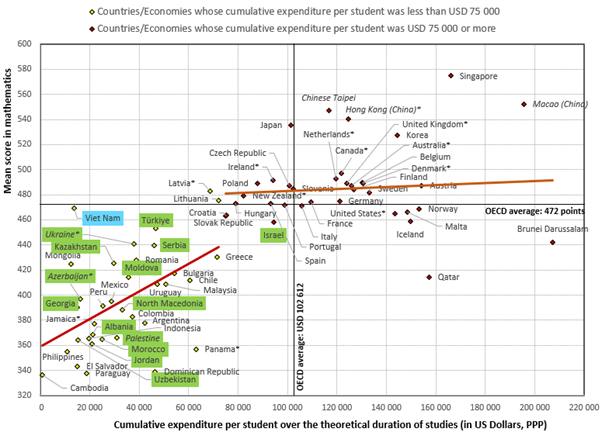

The education and training systems in the countries of the EU neighbourhood differ considerably, reflecting diverse historical, economic and social contexts. However, collectively, these countries have shown a solid commitment to improvement. This is illustrated quite well by the ETF review of education and training developments (ETF, 2023b) and by Torino Process assessments over the years. Yet, most countries face three main challenges that affect the speed at which they integrate green skills and sustainability into their learning outcomes.

- ?7. The road ahead

The energy crisis that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 has accelerated the transition to renewable energy production, significantly influencing the energy landscape of various regions. New markets are appearing and fossil fuels are phased out at an accelerated pace. The shift to renewable energy sources like solar, wind and green hydrogen matches global initiatives to mitigate climate change. Economically, this transition reduces European reliance on imported fossil fuels, which are susceptible to price fluctuations and geopolitical uncertainties. The shift presents both challenges and opportunities for the countries neighbouring the EU. Those rich in renewable resources can find new economic growth avenues in clean energy, those rich in fossil fuel depots may face challenges due to reduced EU demand.

The North African potential for renewable energy is enormous, particularly in solar and wind power. The largest solar park outside of China and India today is Benban Solar Park in Egypt. Its annual production is approximately 3.8 TWh and it was mostly funded through European loans.

This potential not only presents a crucial interim solution to Europe's quest to diversify its energy sources and decrease its reliance on fossil fuels, it also holds promise for long-term energy strategies. North Africa is poised to become a key player in green hydrogen production, which is critical for sectors where decarbonisation is challenging, such as aerospace. The region also has abundant reserves of raw materials that are critical to energy storage and battery technology, offering the EU an avenue to broaden its supply chains for clean energy technologies. The region's young and educated workforce is an asset, not just for potential technology manufacturing closer than Asian markets, but also for collaborative research and development (El-Katiri, L. 2023).

The renewable energy sector in Türkiye is also growing fast, particularly in wind power. The country’s renewable energy capacity has doubled in five years and in 2022, over 40% of the energy it produced came from renewable sources (IEA, 2024). This rapid growth has been driven by robust policy support and financing. Türkiye's upward potential for wind energy is still big, indicating that it could become a regional leader in this field.

Low-carbon energy production also offers significant opportunities for nations in the Western Balkans and the Eastern Partnership, regions that suffer from air pollution linked to energy production.

Promoting renewable energy infrastructure, research and development can generate new job opportunities, especially in sectors such as manufacturing, installation, maintenance and technological innovation. Hence, investment is a critical economic and environmental obligation with strategic opportunities for countries both within and outside the EU.

For instance, Georgia benefits from the EU4Energy programme which supports education and capacity building in the fields of energy efficiency and renewable energy. As another example, Albania already produces 40% of its energy from renewable sources. And Israel has over a quarter of female employees in the energy sector.

Beyond the world of energy, the agriculture sector faces similar challenges and opportunities under the EU's Farm to Fork strategy, part of the European Green Deal, which aims to make food systems more sustainable. By adopting organic farming, neighbouring countries can secure or improve their access to EU markets. Tunisia and Morocco are examples of countries moving in this direction. However, compliance with EU standards and initial price increases pose challenges, potentially affecting their participation in European supply chains and access to finance. This underlines the need for EU support during their transition.

In summary, the green transition offers both challenges and opportunities for the EU's neighbours. Progress towards renewable energy use, sustainable agriculture and a circular economy promise beneficial outcomes but must be carefully navigated to mitigate economic disruption, trade dynamics and political considerations.

- ?8. Conclusions

At this critical juncture, with our planet experiencing significant environmental and socio-economic changes, the importance of the green transition in the EU neighbourhood cannot be overstated. This paper has explored the complex challenges and opportunities ahead, firmly establishing that climate action is an exigent imperative rather than a mere option. Education and labour reforms are cornerstones in this ecological metamorphosis because it needs a workforce skilled in green technologies and sustainability practices.

Our analysis shows that, despite geographic and socio-economic disparities, the transition to a green economy is creating new markets and driving innovation. With renewable energy sources rapidly replacing fossil fuels, countries rich in solar and wind resources stand to redefine their economic landscapes. However, this seismic shift also brings the potential for economic upheaval, necessitating strategic planning and collaborative efforts to ensure an equitable transition.

The success of these policies hinges on the integration of education and skills development with labour market needs, creating a workforce that is resilient to the evolving dynamics of a decarbonised economy.

Moving forward, the paper suggests that merging technical skills with a societal shift towards sustainable living is essential. Given the right education and opportunities, the growing number of young people in the region can lead the way to an economy that genuinely and simultaneously addresses the needs of the environment and the people to achieve lasting peace.

The call to action is clear: harness the transformative potential of education and work for a future that is not only green and resilient but also rich with opportunities for everyone.

- ? References

Banja, M., Belis, C., Djatkov, D., Dobricic, S., Jones, A., Lettieri, T., Muntean, M., Paunovic, M., Niegowska, M.Z., Marinov, D., Pozzoli, L., Poznanović, G., Vandyck, T., Wojda, P. & Zdruli, P. Status of environment and climate in the Western Balkans, EUR 31077 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2022), ISBN 978-92-76-52722-0, doi:10.2760/374068, JRC129172.

Cedefop (2023), Skills in transition: the way to 2035. EU Publications Office, Luxembourg.

Chiciudean, D.I., Chiciudean, G.O., Mureșan, I.C., Shonkwiler, V.P. & Zaharia, A. (2024), Exploratory study of Romanian generation Z perceptions of green restaurants. Adm. Sci. 2024 14, 21.

Circle Economy Foundation and Deloitte, 2024, Circularity Gap Report 2024, Circle Economy Foundation.

COACCH (2018), The economic cost of climate change in Europe: synthesis report on state of knowledge and key research gaps. Policy brief by the COACCH project. Editors: Paul Watkiss, Jenny Troeltzsch, Katriona McGlade.

El-Katiri, L. (2023), Sunny side up: maximising the European Green Deal’s potential for North Africa and Europe, European Council on Foreign Relations.

ETF (2022), Skills mismatch in ETF partner countries, European Training Foundation, Turin.

ETF (2023a), Skilling for the green transition - policy brief.

ETF (2023b), Education, skills and employment 2023 – trends and developments.

ETF (2023c), The future of skills in ETF partner countries - Cross-country reflection paper: a multifaceted innovative approach combining big data and empirical research methods.

Fátima Alves et al (2020), ‘Climate change policies and agendas: Facing implementation challenges and guiding responses’, Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 104, 2020, Pages 190-198, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Freedom House (2024), Freedom in the world, Freedom House, Washington DC.

Gass et al (2021), International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Employment, Economic, and Social Consequences of the Transition to an Ecologically Sustainable Economy in Developing Countries. GIZ: Eschborn.

He, Z., Chen, Z. & Feng, X. (2023), The role of green technology innovation on employment: does industrial structure optimization and air quality matter? Environmental Sciences Europe, vol 35, 59, Springer.

Hejazi, Mohamad and Santos Da Silva, Silvia R. and Miralles-Wilhelm, Fernando and Kim, Son and Kyle, Page and Liu, Yaling and Vernon, Chris and Delgado, Alison and Edmonds, Jae and Clarke, Leon, (2023), Impacts of water scarcity on agricultural production and electricity generation in the Middle East and North Africa - Frontiers in Environmental Science – Vol 11, Frontiers.

ICRC (2023), Making adaptation work – Addressing the compounding impacts of climate change, environmental degradation and conflict in the Near and Middle East, International Committee of the Red Cross and Norwegian Red Cross.

IEA (2023), World Energy Outlook 2023, IEA, Paris.

IEA (2024), Electricity 2024, IEA, Paris.

ILO (2019), Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work International Labour Office – Geneva.

IPCC (2022), Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S. , Löschke, S., Mintenbeck, K., Möller, V., Poloczanska, E.S., Pörtner, H., Okem, A., Rama, B., Roberts, D.C. & Tignor, M. (eds.), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

IRENA (2020), Power sector planning in Arab countries: Incorporating variable renewables, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi.

Seto, K. et al (2016) - Carbon Lock-In: Types, Causes, and Policy Implications - Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2016 41:1, 425-452.

Kioupi, V., & Voulvoulis, N. (2019). "Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216104.

Kleimann, D. (2023), ‘Climate versus trade? Reconciling international subsidy rules with industrial decarbonisation’, Policy Contribution 03/2023, Bruegel.

Kountouris, I. (2023), UN SDSN Global Climate Hub: Modelling Net Zero Pathways.

Aggarwal, A., Comyn, P.J., Hoftijzer, M., Iqbal, S., Katayama, H., Levin,V, Santos, I.V. & Weber, M. (2023), Building better formal TVET systems: Principles and practice in low- and middle-income countries. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Lola Nacke, L., Cherp, A. & Jewell, J. (2022), Phases of fossil fuel decline: Diagnostic framework for policy sequencing and feasible transition pathways in resource dependent regions, Oxford Open Energy, Volume 1, 2022, oiac002.

Markard, J., Raven, R. & Truffer, B. (2012), Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955-967.

McKay et al (2022), ‘Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points’ Science. 2022; 377eabn7950.

OECD (2023), Job creation and local economic development 2023: bridging the great green divide, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning during – and from – disruption, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Pew Research Center (2021), ‘Gen Z, millennials stand out for climate change activism, social media engagement with issue’, Pew Research Center, Washington DC.

PwC (2023), Green jobs barometer 2023 – Green jobs and opportunities: in pursuit of a competitive and equitable green jobs market, PwC.

Sachs, J.D., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G. & Drumm, E. (2023), Implementing the SDG Stimulus – Sustainable development report 2023, 10.25546/102924, SDSN, Paris, Dublin University Press, Dublin.

Tyros, S., Andrews, D. & de Serres, A. (2023), ‘Doing green things: skills, reallocation, and the green transition’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1763, OECD Publishing, Paris.

UNFCCC (2023), Conference of the parties serving as the meeting of the parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA) - Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement. Synthesis report by the secretariat. UN climate change conference - United Arab Emirates Nov/Dec 2023. FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/12.

WMO (2023), Provisional state of the global climate 2023, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva.

Other articles

Experts from outside the ETF have contributed to this collection of ETF articles with first-hand experience from their own very colourful patchwork of work environments. See also below.