As previously mentioned, human capital is an aggregate of the knowledge, skills, talents and abilities of individuals that they can use for economic, social and personal benefit. The value of human capital depends on how well it is being developed, and the extent to which it is then available and used. Table 2 presents a selection of HCD indicators, providing a basic overview of how Moldova is performing in this respect.

The country is confronted with a considerable demographic disadvantage as a result of the ageing population and emigration. At the same time, projections suggest that the problem will have a limited impact on the demographic structure of the population of working age over the coming years (Table 2, Indicator 1). However, this also means that the population-related challenges relating to human capital that the country was facing at the time of this assessment, such as workforce depletion, are likely to persist in future years.

Table 2 also shows that young people of school age spend almost four years longer in formal education than the time they are actually learning (Indicators 2 and 4), which points to problems with the effectiveness of teaching and learning. Nevertheless, Moldova ranks in the upper half of the Global Innovation and Digital Readiness indices of the World Economic Forum (WEF) (Indicators 6 and 8), which suggests that the workforce and its HCD circumstances have a potential that can be developed and leveraged to the benefit of all. At the same time, there is a considerable degree of wastage in this area. A fifth of the higher education graduates in Moldova – who are also those with the longest and thus most costly educational careers – work in occupations that are not related to the education in which the state has been investing (Indicator 9).

Table 2. Selected indicators of human capital

|

Year |

Value |

|

|

(1) Population structure (% of total) |

||

|

0 - 24 |

2015 |

29.9% |

|

25 - 64 |

2015 |

60.2% |

|

65+ |

2015 |

9.9% |

|

0 -24 |

2025* |

25.3% |

|

25 - 64 |

2025* |

59.8% |

|

65+ |

2025* |

14.9% |

|

(2) Average years of schooling |

2017 |

11.6 |

|

(3) Expected years of schooling |

2017 |

11.6 |

|

(4) Learning-adjusted years of schooling |

2017 |

8.2 |

|

(5) Adult literacy |

2015 |

99.4% |

|

(6) Global Innovation Index Rank (x/126) |

2018 |

48 |

|

(7) Global Competitiveness Index Rank (x/137) |

2017 - 18 |

88 |

|

(8) Digital Readiness Index Rank (x/118) |

2018 |

49 |

|

(9) Occupational mismatch |

||

|

% of upper-secondary graduates working in low-skilled jobs (ISCO 9) |

2016 |

14.0% |

|

% of tertiary graduates working in semi-skilled jobs (ISCO 4-9) |

2016 |

21.8% |

* Projection.

Sources: (1) UN Population Division, World Population Prospects, 2017 revision; (2) UNESCO, UIS database; (3) and (4) World Bank (2018), Human Capital Index; (5) UNESCO, UIS database; (6) WEF, Global Innovation Index, 2018; (7) WEF, Global Competitiveness Index 4.0, 2018; (8) Cisco, Country Digital Readiness, 2018; (9) ETF, skills mismatch measurement in the ETF partner countries.

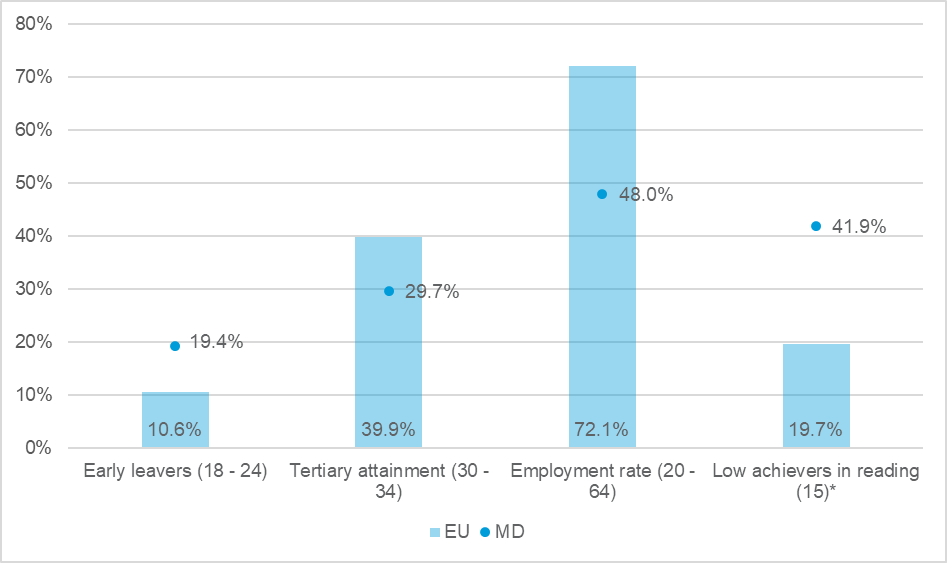

The EU benchmarks complement this picture with additional detail (Figure 1). They show that the share of people with tertiary education attainment is still low by international comparison, perhaps because close to a fifth of students leave school early, twice the EU average. Those young people who remain in formal education and training will struggle with the low quality of education they receive, and over 40% of them will be classified as low achievers by the end of their compulsory schooling.

Figure 1. EU benchmarks in education and training (%)

Note: *Year of reference 2015.

Source: ETF database.