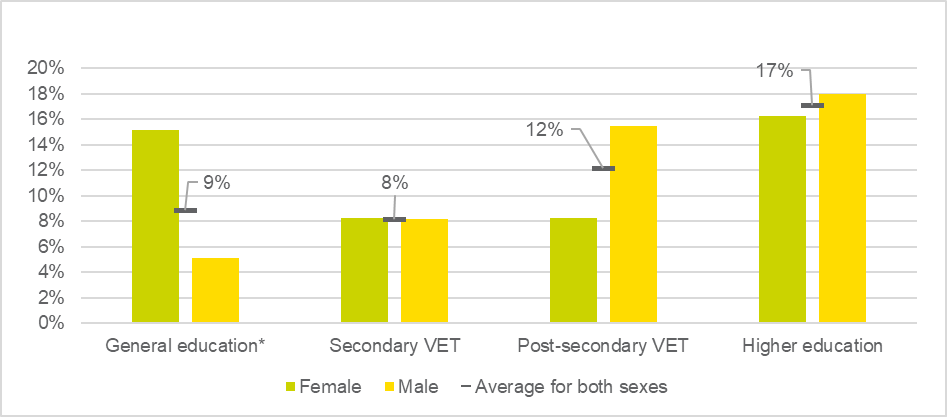

This chapter discusses two further problems relating to human capital in Moldova: the depletion of human capital as a result of migration and the exclusion of young people from employment and educational opportunities. These challenges are assessed in greater detail because, in the view of the ETF, they require immediate attention: they are major impediments to progress on Moldova's strategic priorities towards more and better employment and productivity, and the removal of all human-capital-related constraints on growth.

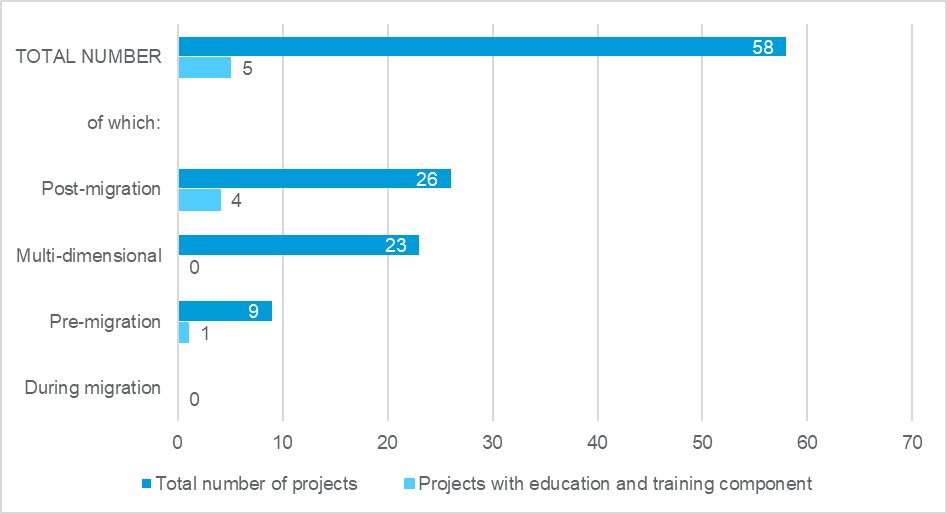

These two problems have in common the fact that they have both been addressed through a wide range of rather complex policy responses that rely on education and training, but that seem to neglect the youth segment of the population they target. The more detailed analysis of the reasons for these problems and the overview of possible shortcomings in the policies that are intended to address them may help with the ongoing efforts in Moldova to design the next generation of strategic plans and policies up to 2030, in line with the country's national and international commitments.

Moreover, the two problems are interconnected, and progress with one, for instance greater participation of young people in education and employment, will also indicate progress with the other, that is, the prevention of human capital depletion as a result of migration.