This report has previously noted that human capital is an aggregate of the knowledge, skills, talents and abilities of individuals, which they can use for economic, social and personal benefit. The value of human capital depends on how well it is developed and the extent to which it is then available and used. Table 2 presents a selection of human capital development indicators that give a basic overview of how Jordan is doing in this respect.

Table 2. Selected HCD indicators, Jordan

|

Year |

Value |

Rank |

|

|

(1) Population structure (% of total) |

|||

|

0-14 |

2018 |

34.1% |

|

|

15-64 |

2018 |

62.3% |

|

|

65+ |

2018 |

3.5% |

|

|

(2) Average years of schooling |

na |

||

|

(3) Expected years of schooling |

2017 |

11.62 |

|

|

(4) Learning-adjusted years of schooling |

2017 |

7.61 |

|

|

(5) Adult literacy |

2018 |

98.2% |

|

|

(6) Global Innovation Index Rank (x/126) |

2019 |

29.61 |

86 |

|

(7) Global Competitiveness Index Rank (x/137) |

2019 |

60.9 |

70 |

|

(8) Digital Readiness Index Rank (x/118) |

2019 |

12.14 accelerate |

68 |

Sources: (1) UN Population Division, World Population Prospects, 2017 revision; (2) UNESCO, UIS database; (3) and (4) World Bank (2018), Human Capital Index; (5) UNESCO, UIS database; (6) WEF, The Global Innovation Index, 2018; (7) WEF, Global Competitiveness Index 4.0, 2018; (8) Cisco, Country Digital Readiness, 2018; and (9) ETF, skills mismatch measurement in the ETF Partner Countries.

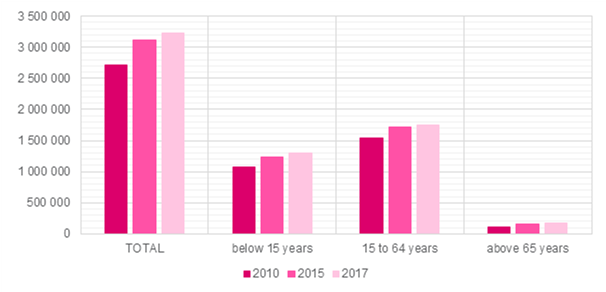

The population of Jordan is predominantly young: in 2018, over one-third (34.1%) was under the age of 15, which is relatively high in international comparison. For instance, the average share of youth in the same age group was only 15.6% in the EU in 2018. There is also a sizeable share of people of working age (62.3%), while those of retirement age and beyond accounted for only 3.5% of the population, which is over 5.6 times lower than the EU average (19.7%).

Considering the size of the school-age population and the associated pressures on the enrolment capacity and budget of the education and training sector, Jordan is doing remarkably well in safeguarding access to education and graduation chances for young people. On average, students can expect to receive 11.62 years of schooling, albeit of limited quality and effectiveness (11.62 years of schooling translate to only 7.61 years of learning).

Nevertheless, the rate of adult literacy is high (98.2%), the country ranks in the upper half on the list of global competitiveness (ranking 10th out of 137 countries), and it is gaining ground in terms of digital readiness as measured by the Digital Readiness Index.