The geopolitical and socio-economic background described in Chapter 1 forms a very specific context for human capital development in Palestine. With limited room for manoeuvre to relax access restrictions and low expectations for any improvement in the overall macroeconomic climate, it is crucial to understand the specific challenges better in order to make the best use of Palestine's main resource, namely its human capital. This chapter will provide a brief overview of a number of the challenges.

Policies for human capital development in Palestine

Breadcrumb

- Domov

- Publications & resources

- Publications

- Torino Process reports

- Current: Policies for human capital development in Palestine

An ETF Torino Process assessment

2.1 Managing human capital in an archipelago economy is a disjointed exercise of matching localised skills demand and supply

The labour market is highly segmented in Palestine, not only by age and gender, but also geographically as a result of its archipelago economy. In addition, the administrative separation between the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem and Israel leaves its mark[44] The administrative separation between Gaza and the West Bank has taken various forms since 2007, with more or less collaboration between the physically separate territories. Over the same period, East Jerusalem has witnessed gradually increasing isolation from the administration in the West Bank in terms of labour market and social welfare issues.

.

TABLE 6. PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF EMPLOYED INDIVIDUALS (AGED 15+) BY GENDER AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY, 2019

|

Gender and region |

Agriculture |

Mining & manufacturing |

Construction |

Commerce, hotels & restaurants |

Transportation, storage & communication |

Services & other branches |

Total |

|

|

Total |

||||||||

|

Palestine |

6.3 |

13 |

17.7 |

21.7 |

6.2 |

35.1 |

100 |

|

|

West Bank |

6.5 |

14.4 |

22.3 |

22.8 |

4.9 |

29.1 |

100 |

|

|

Gaza Strip |

4.7 |

6.2 |

3.3 |

22 |

8.6 |

55.2 |

100 |

|

|

Jerusalem |

0.5 |

12.7 |

21.9 |

27.1 |

8.4 |

29.4 |

100 |

|

|

Males |

||||||||

|

Palestine |

6.2 |

13.8 |

20.9 |

23.6 |

6.9 |

28.6 |

100 |

|

|

West Bank |

6.2 |

15.6 |

26.4 |

24.6 |

5.5 |

21.7 |

100 |

|

|

Gaza Strip |

5.3 |

6.7 |

3.9 |

25.1 |

9.9 |

49.1 |

100 |

|

|

Jerusalem |

0.5 |

14.4 |

25.4 |

29.9 |

9.4 |

20.4 |

100 |

|

|

Females |

||||||||

|

Palestine |

6.8 |

9 |

0.3 |

11 |

2.2 |

70.7 |

100 |

|

|

West Bank |

8.4 |

8.1 |

0.7 |

13.1 |

1.7 |

68 |

100 |

|

|

Gaza Strip |

1.7 |

3.4 |

0 |

5.2 |

1.6 |

88.1 |

100 |

|

|

Jerusalem |

0.3 |

3.1 |

2.3 |

11.3 |

3 |

80 |

100 |

|

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

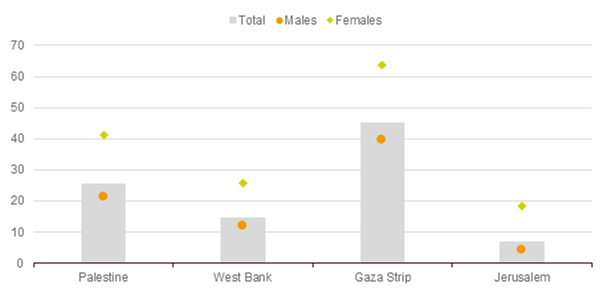

Each island economy has its own labour market characteristics in terms of labour demand, skills needs and wage levels. Compared to the West Bank, the Gaza Strip performs markedly worse on virtually all measurable labour market indicators, reporting higher unemployment rates, lower activity and employment rates, lower wages and a smaller private sector. Moreover, the differences between the situation of Palestinians in the domestic labour market and those working in Israel are even more pronounced.

FIGURE 8. UNEMPLOYMENT RATE BY REGION AND GENDER, 2019

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

In such a context, clear forecasting and reliable labour market statistics are a challenge, not least in order to achieve a sufficient level of disaggregation to assess the skills demand in an already small labour market. Over the past decade, several international actors in the VET arena have tackled labour market needs and skills anticipation through employer surveys and training needs assessments. A 2015 survey by AWRAD & CARE describes the skills mismatch as follows: '[t]he vast majority of business owners state that they have varying degrees of difficulty filling job vacancies, and many continue to say they place greater faith in the skills of old staff, indicating the problem is growing. This has forced the majority of firms to hire employees who do not meet the minimum requirements for the job'[45] AWRAD & CARE 2015, p. 7

.

A number of reports confirm that the mismatch is highly dependent on the region: 'East Jerusalem businesses report the greatest difficulty in filling vacancies, while Area C employees and graduates report the greatest difficulty in finding work'. Interpreting the data is another matter. The previous statement does not necessarily mean that the East Jerusalem economy is thriving. Rather, it is more closely related to the fact that over half of the Palestinians in East Jerusalem are employed in Israel. The difficult access to jobs for Area C residents is undoubtedly related to the restrictions imposed on Area C, which force residents to be more mobile: 'residents of Area C are more likely to leave their locales looking for jobs than their counterparts in areas A and B'[46] AWRAD & CARE 2015, p. 9; GIZ 2015, pp. viii, 35 and 64

.

The labour market in Gaza is highly affected by economic constraints relating to omnipresent access restrictions (including on import materials), military limitations on land use and coastal waters, and export limitations. Nevertheless, a number of studies still see some potential for economic development and job creation. A labour market needs assessment conducted by the Belgian Development Agency in 2016 using an employability matrix indicates that 'the most promising economic sectors for TVET employment and entrepreneurship in the current business environment in the Gaza Strip are: the services sector, the agriculture and fishery sector, and the information and communication technology (ICT) sector'[47] BTC 2016, p. 2; GIZ 2015, pp. 61–62

. What are the opportunities for proactive human capital development measures to boost sector development before overheating and saturating the various areas' respective limited job markets? Recent tracer studies show more promising figures for the transition to employment among VET graduates (particularly graduates of WBL programmes) than among their peers with university diplomas. Consequently, despite the overall economic situation, there is reason to believe that VET training can be part of a better skills supply. Analysing PCBS labour force data[48] In the PCBS labour force survey, there is a question that asks participants whether they have attended a vocational training course.

with a linear probability model, AWRAD & CARE investigated the effect of attending training courses on the probability of gaining employment and found that 'on average, a person who has taken the training course was 12.13% more likely to be employed, taking into account gender, level of education, age and industry'[49] NR 2020 p. 39; AWRAD & CARE, p. 29

.

However, transition to employment is far from straightforward for VET graduates, as many employers still find a significant skills gap. Significant efforts have been made over the past decade to enhance the relevance of VET in Palestine, but the VET system remains rigid and requires efforts to understand labour market needs better, adapt training to improve the employability of graduates, and work on the private sector's perception of VET graduates. In view of Palestine's archipelago economy, the system should be more agile and adaptable to accommodate the different geographic realities and maximise the employability potential in view of sector needs and opportunities at the local level. This is as much the case for industrial development in Hebron and the platform economy in Gaza as it is for the most vulnerable and marginalised, e.g. food-insecure residents in Gaza or Area C[50] BTC 2016. p. 2; GIZ 2015, pp. 61–62

.

2.2 Job informality in a grey economy: the blind spot in managing human capital development stock

The Torino Process national report indicates that the informal economy and job informality play a significant role in the Palestinian labour market. Various sources including the ILO and World Bank indicate that more than one out of every two workers in Palestine are hired informally, while PCBS classifies 62% of workers as informal (2016 data). Both the enormous volume of informality and the lack of clear data raise questions about the reliability of overall labour market information in Palestine, indicating that there might be underreporting or misinterpretation of the actual labour force.

Job informality is especially, but not solely, to be found in the informal sector. The definition of 'informality' is not universally agreed. The 17th International Conference for Labour Statisticians (ILO, 2003) defined informal employment more broadly to include 'informal' employees who work for formal or informal economic units without being registered or declared by their employers. While the informal sector refers to the informal link between the state and the business owner, informal employment refers to the informal link between employer and employee (affecting job precariousness, risks, quality, and working conditions)[51] The concept of the 'informal sector' refers to production units as observation units, while the concept of 'informal employment' refers to jobs as observation units. The criteria for informal employment include the absence of a written contract, no pay slip, no legal or social protection, outworkers (home-based workers, street workers), a casual/temporary job and the absence of a labour union.

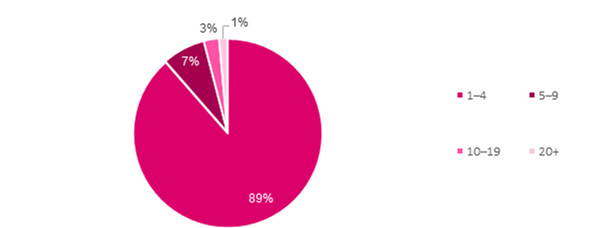

. Given the high level of self-employment (24.6% overall, 26.6% for men and 14.5% for women) (PBCS, 2019) and the predominance of micro-enterprises (89% of companies have fewer than 5 employees) in the Palestinian economy (PCBS, 2017 data), the definition of an informal establishment used by PCBS[52] The PCBS uses the following definition of an informal establishment: an establishment that employs fewer than or equal to five employees, who are mostly proprietors (note that professionals such as doctors, engineers, auditors and all other related professions are excluded from the survey frame). In addition, they engage unpaid family members and have a low value of capital, a lack of complete accounting records, a lack of work contracts, etc.

could apply to a majority of businesses in Palestine and even bring most of them into the informal sphere. In this regard, the World Bank cites a longitudinal study by Sabra, Eltallar and Alfar (2015) that finds for the period 1995–2012 that the shadow economy – composed of informal activities – accounted for 58–89% of GDP in Palestine[53] Red tape and cumbersome business regulations are cited among the reasons for the prevalence of informality: 'the process of registering a business is complicated, lengthy and unclear. There is no automated business registration system and lawyers provide inconsistent information to entrepreneurs. Registration categories are confusing, and entrepreneurs often register their businesses under incorrect categories or choose to register in foreign countries. As a result, many businesses choose to operate informally. While there have been some important recent reforms, such as the streamlining of municipal business licensing and the registration of business property, the reform process has been slow, piecemeal, uncertain, and with limited input from the private sector. This approach has done little to gain the trust of the business community regarding the government's regulatory reform efforts. A Big Bang regulatory reform would send a clear signal to the business community that the PT are open for business'. While this recommendation was put forward to boost tradable services in a digital economy, it is also relevant for businesses in Palestine (WB 2019c, pp. 17, 31–32; BTC 2015, p. 54).

.

FIGURE 9. PERCENTAGE OF ESTABLISHMENTS BY NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES, 2017

Source: PCBS, Population, Housing and Establishments Census 2017

Citing the FAO[54] FAO (2011). 'Palestinian Women's Associations and Agricultural Value Chains', Case Study Series No. 2

, AWRAD & CARE note that 'the agriculture sector is largely informal and is therefore underrepresented in official employment statistics. FAO estimates that the agriculture sector provides work for 305 250 individuals – as of 2011 – and represents “more than 39 percent of those working in informal sectors and supporting a significant proportion of Palestinian families who cultivate their lands for their livelihood”'[55] AWRAD & CARE 2015, p. 33

. However, job informality is also a reality for at least one out of every two Palestinians employed in other sectors. This is likely linked to the dominance of family-run micro-enterprises in which sons, nephews, cousins or more distant relatives are employed, regardless of their skill set. In this regard, GIZ refers to the importance of 'real or perceived “family business secrets”'[56] The Arabic word to describe a certain expertise or 'business secret' is اسرار المهنة, which means 'secrets of the profession' (GIZ 2020, p. 3).

that make it 'difficult for sharing craft skills with an outsider like an apprentice or an intern'[57] A 2015 qualitative study by BTC traced a sample of recent graduates from TVET institutions in the West Bank and East Jerusalem to understand what prevents the hiring process for TVET graduates from being competency-based. The study examined the relevance of five main factors (labour market segmentation, information failure, nepotism ('wasta'), skills mismatch and working conditions) and found that the vast majority of respondents agreed with the statement that '[n]epotism plays a large role in determining hiring decisions, frequently favouring family members over other more qualified applicants. The fact that a majority of Palestinian businesses are small and owners want to keep them in the family plays a large role' (BTC 2015, pp. 3, 19).

.

Job informality primarily affects the most vulnerable. It is exceptionally high among young workers. The World Bank cites an ILO estimate of 2014, which found that 94% of young workers (aged 15–29) were employed informally. Research also shows that workers with a semi-skilled or low-skill profile have a high chance of ending up in an informal set-up and that this is the case for both sexes in Palestine. The World Bank notes that 'the few female workers with secondary education or below who did not drop out of the labour market are largely employed informally (73%)', while the figure for their male counterparts is 67%. In contrast, the figures for working informally are significantly lower for skilled people: 'in 2015 only 4% of employed skilled females and 11% of employed skilled males worked in an informal firm'. Overall, the size of the grey job market in Palestine is worrying job informality undermines worker protections (both legally and in terms of decent work) and labour productivity (unreliable accountability)[58] WB 2019c, p. 17; WB 2018a, pp. viii, 14

.

2.3 Palestinian labour mobility to the Israeli economy: a key exogenous element with an impact on the domestic usage of human capital

Roughly 13.3% of active Palestinians (PCBS, 2019) are employed in Israel or Israeli settlements. An UNCTAD report in 2019 indicates that 'the incapacity of the restrained economy, under occupation, to generate jobs, in the face of a growing population, forces a high number of Palestinians to seek employment in Israel and settlements in the West Bank, which are illegal under international law (as noted in Security Council resolution 2334)'.

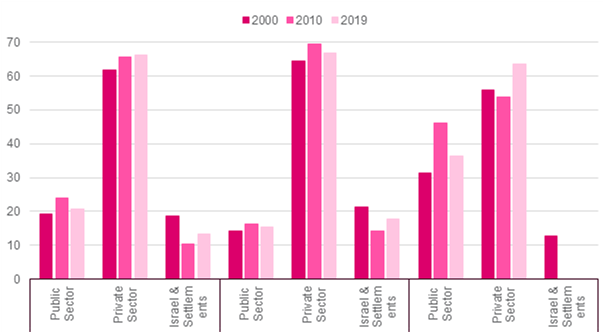

FIGURE 10. PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF EMPLOYED PEOPLE (AGED 15+) BY REGION AND SECTOR, 2000–2019

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

*Since 2006, Gaza Strip employees have not been able to access Israel and Israeli settlements.

Palestinian employment in the Israeli economy has a long history and is a significant factor to take into account when addressing either the Palestinian labour market or the Israeli economy. In the past, the Israeli construction sector in particular has been heavily dependent on it. The majority of workers are employed in low-skilled labour. In its literature review on the subject, the AWRAD & CARE study concludes that since the 1980s, the majority of work permits have gone to construction workers, followed by agricultural workers and, to a lesser extent, industry and services[59] AWRAD & CARE, p. 22; WB 2019c, p. 18

.

While it is beyond the control of the Palestinian labour market, labour mobility to the Israeli economy is a key exogenous element that has an impact on the domestic usage of human capital. In recent decades, cross-border labour mobility has fallen significantly owing to increasing restrictions by Israel's security apparatus (the construction of a separation barrier, the reduced number of work permits, the unpredictability of operating hours and security checks at checkpoints, etc.), which further exacerbate unemployment levels in Palestine. According to the World bank, '[t]hese restrictions have resulted in more than one-third of Palestinians working illegally in Israel and, particularly, the settlements.'[60] World Bank, 2019c, p.18.

Although the share of Palestinians working in Israel and the settlements has increased to 13.2% (up from 10.5% in 2010), it is still far below the 2000 level of 18.8%, which was already lower than pre-Oslo levels[61] During the Covid-19 emergency, an estimated 50 000 Palestinian informal workers were active in the Israeli market and prone to job losses in the absence of any formal arrangement.

.

Taking into account that the mobility of workers from Gaza has come to a complete standstill since the blockade in 2007, the current figures relate only to West Bank workers (17.8% of the West Bank workforce). According to the World Bank, this figure could be even higher since it is 'well below the demand for Palestinian labour in Israel and the settlements and the number of Palestinians willing to work there attracted by significantly higher wages'. Wages are considerably higher (ILS 254.4) and more than double the wages in Palestine (ILS 110.8 in the public sector and ILS 96.6 in the private sector). However, higher educational attainment does not correspond to higher wages[62] UNCTAD 2019, pp. 4–5; WB 2019c, p. 18

.

TABLE 7. AVERAGE DAILY WAGE IN ILS FOR WAGE EMPLOYEES (AGED 15+) BY REGION AND SECTOR, 2000-2019

|

Region and sector |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2019 |

|

Palestine |

|||||

|

Public sector |

59 |

70.4 |

85.2 |

99.7 |

110.8 |

|

Private sector |

66.8 |

67.4 |

74.3 |

75.7 |

96.6 |

|

Israel & settlements |

110.5 |

125.6 |

158 |

199.5 |

254.4 |

|

Average daily wage |

76.6 |

77 |

91.7 |

103.8 |

128.6 |

|

West Bank |

|||||

|

Public sector |

62.9 |

71.5 |

90.5 |

108.1 |

120.6 |

|

Private sector |

73.7 |

74.1 |

83.6 |

88.6 |

118.3 |

|

Israel & settlements |

108.6 |

125.4 |

158 |

199.5 |

254.3 |

|

Average daily wage |

82.8 |

84.4 |

102 |

120.6 |

151.7 |

|

Gaza Strip |

|||||

|

Public sector |

55.2 |

69.4 |

74 |

85 |

93.4 |

|

Private sector |

49.2 |

51.9 |

48.7 |

51 |

44.1 |

|

Israel & settlements |

117.2 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Average daily wage |

64.1 |

62.3 |

58.2 |

62.3 |

61.4 |

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

*Since 2006, Gaza Strip employees have not been able to access Israel and Israeli settlements.

In an academic paper, a research group at the Humboldt University of Berlin conducted economic modelling to predict the effects on the West Bank economy of eventual restoration of Palestinian employment in Israel to its pre-intifada level (1999). Putting aside any political implications of a final settlement agreement or issues related to brain drain[63] 'The model does not account for the loss of experience caused by those moving out of the domestic market that the new entrants lack' (Agbahey et al. 2018, p. 17).

, the group's theoretical modelling shows 'a strong reduction in Palestinian unemployment, strong welfare improvements for households, and substantial changes in the composition of the labour force in the domestic labour market'. At the macroeconomic level, the model predicts an increase in household income by on average 13%, an increase in welfare for households by on average 7%, and a GDP increase of almost 5%. Another finding of the study is that the extra demand for Palestinian labour in Israel triggers changes in domestic employment in two ways. First, those who switch out of domestic employment are replaced by previously unemployed workers. Second, the additional inflow of labour income from Israel stimulates household consumption and ultimately domestic production. For the expansion of domestic production, more unemployed labour is brought into employment. The net effect is an increase of 5% in domestic employment. In particular sectors, such as construction, these findings might need to be adjusted if the numbers of workers leaving for employment in Israel are bigger than the unemployment stock of qualified candidates and they might even result in pushing up wages in a particular sector[64] Agbahey et al. 2018, pp. 1, 20–23

.

UNCTAD sheds light on the gender aspect of labour mobility to Israel: '[a]n overwhelming 99 percent of them are men, classified as low-skilled by educational attainment, with less than 13 years of schooling', according to 2018 data from the Economic Policy Research Institute, PCBS and Palestinian Monetary Authority. By contrast, the modelling in the Humboldt University study predicts that 'in the Palestinian context, increasing labour supply to Israel has a strong effect on female employment in the domestic market. Moreover, relatively more high-skilled workers move into employment in the domestic market, which is a good outcome for the domestic production system'[65] UNCTAD 2019, pp. 4–5; Agbahey et al. 2018, p. 23

.

2.4 Female, skilled and underemployed: a loss to the human capital of Palestine

Over the years, almost complete gender parity in education has been achieved in Palestine, with women outperforming men at tertiary education level since 2015. In 2019, 23.6% of women held a tertiary degree, compared to 20.5% of men (PCBS). However, the same cannot be said of participation in the labour market. While the other parameters remain the same (the availability of jobs is limited in Palestine for both sexes alike and young people suffer more than older age groups), men outperform their female counterparts disproportionately on every labour force indicator.

FIGURE 11. LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION INDICATORS BY GENDER AND AGE, 2019

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

More worrisome is that the gender divide worsens with an increase in education level, turning highly skilled women[66] In the World Bank study, in more general terms, skilled workers are defined as those holding a postsecondary education, which includes a two-year associate degree. Therefore, workers who finish a postsecondary education and join the labour market in search of employment can be as young as 19 (students in the Palestinian territories finish high school at 17)' (WB 2018a, p. 7).

into a marginalised segment of the labour market. While a Palestinian woman who is well educated has a better chance to get a job (the employment rate is 31.2% for women with a tertiary degree), it is still well below her male counterparts with the same diploma (71.5%). One out of every two women with a tertiary degree who is active in the labour market (47.6%) struggles to find a job (PCBS, 2019). In Gaza, women with more than 13 years of schooling face a staggering unemployment rate of 65.5% (almost twice as high as the rate for men with the same diploma level at 33.7%) and the figure is 32.6% in the West Bank (four times higher than the rate for men at 8.4%)[67] WB 2018a, pp. vii–viii, 10, 47

.

TABLE 8. UNEMPLOYMENT RATE (AGED 15+) BY GENDER AND YEARS OF SCHOOLING, 2019

|

Years of schooling |

Total |

Male |

Female |

|

|

Palestine |

0 |

19.4 |

28.7 |

6.6 |

|

6-1 |

21.6 |

22.7 |

9.8 |

|

|

9-7 |

22.6 |

23.0 |

15.4 |

|

|

12-10 |

22.1 |

22.0 |

23.4 |

|

|

+13 |

30.0 |

18.9 |

47.2 |

|

|

West Bank |

0 |

10.4 |

18.6 |

0.3 |

|

6-1 |

13.5 |

14.8 |

2.7 |

|

|

9-7 |

13.2 |

13.7 |

4.5 |

|

|

12-10 |

12.8 |

13.0 |

8.9 |

|

|

+13 |

17.6 |

8.4 |

32.6 |

|

|

Gaza Strip |

0 |

41.2 |

50.0 |

25.6 |

|

6-1 |

38.5 |

38.0 |

50.1 |

|

|

9-7 |

45.2 |

44.9 |

53.7 |

|

|

12-10 |

44.2 |

43.3 |

54.4 |

|

|

+13 |

46.7 |

33.7 |

65.5 |

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

Within the context of a highly segmented economy, the World Bank finds that 'skilled men and women do not compete for the same jobs – the jobs available to skilled women are far more limited than those available to skilled men'. First of all, skilled women (more so even highly skilled, qualified or specialist) are highly overrepresented in the public sector (the majority were employed in the education sector in 2015, and the total reaches 79% if women in the healthcare sector, social work and public administration are added) and seriously underrepresented in the private sector. The World Bank finds that '[f]ull-time female workers made up only 2.9 percent of all workers in medium-sized enterprises in the private sector in 2013'. This might be related to other changes in the economy, given that the 'two productive sectors that tend to employ women ⎯ agriculture and manufacturing ⎯ have seen a steep decline over the past decade as a result of the systematic restrictions on access to land, water, and imports and exports'. However, women have clearly been forced into a small number of occupations as well: '[b]ecause they are in the non-growth areas of the economy, these sectors have reached their limits in absorbing women'[68] WB 2018a, pp. ix, 19–20, 24–25.

.

In addition, women do not appear to be working for the same salaries as their male counterparts. They receive an average daily wage of ILS 98.6, which is one-third less than their male counterparts (ILS 134.4). The gender difference in salaries is most dramatic in the mining, quarrying and manufacturing sector, where women earn ILS 61.8, which is half the wage of their male counterparts (ILS 119) (PCBS, 2019 data).

TABLE 9. AVERAGE DAILY WAGE IN ILS FOR WAGE EMPLOYEES (AGED 15+) BY ECONOMIC ACTIVITY AND GENDER, 2019

|

Total |

Males |

Females |

|

|

Agriculture, hunting & fishing |

89.6 |

90.0 |

76.7 |

|

Mining, quarrying & manufacturing |

115.2 |

119.0 |

61.8 |

|

Construction |

212.1 |

212.4 |

- |

|

Commerce, hotels & restaurants |

96.2 |

98.2 |

69.9 |

|

Transportation, storage & communication |

91.7 |

91.8 |

91.3 |

|

Services & other branches |

113.8 |

118.8 |

103.7 |

|

Average daily wage |

128.6 |

134.4 |

98.6 |

Source: PCBS 2020, LFS

The importance of social capital should not be underestimated. Locally referred to as wasta, which can be loosely translated as 'connections' in seeking a job, social capital is one of the most frequently cited drivers of mismatches in employment. Youth with limited social capital, particularly young women, are the most affected. To understand better the gender bias around female access to employment, a series of quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted over the years, giving rise to a long list of gender specific constraints that keep women out of the workforce. The constraints include legislation (married women need permission from their husband to get a job, there is a lack of legislation against sexual harassment in the workplace, there are restrictions on nights shifts for women, etc.), logistics issues (e.g. the lack of access to affordable quality childcare, the lack of safe and reliable transportation, etc.) and a set of cultural norms (blue-collar jobs are 'not for women', the double burden on working moms[69] ”Women talked about their double burden of professional and domestic responsibilities and their feelings of guilt at not being able to perform well in their main, socially-prioritized role as mothers.” UN-WOMEN 2017 p221.

, a stay-at-home mom stereotype[70] “Inequitable gender attitudes remain common in Palestine, although women hold more equitable views than men do. For example, around 80 per cent of men and 60 per cent of women agree that a woman's most important role is to take care of the home.” UN-WOMEN 2017 p. 198.

, a male breadwinner stereotype[71] ”Around 83 per cent of men and 70 per cent of women agreed that men's access to work should take priority over women's when such opportunities are scarce“. UNWOMEN 2017 p208.

and the persistent belief that women will work for less pay)[72] UNESCO 2019: p.2; WB 2018a p.27-40, UNWOMEN 2017 p198, 208-221; BTC 2015, p36.

.

The underemployment of the skilled female workforce is first and foremost a hardship for young women. It prevents them from building a meaningful career and contributing to a household economy. Since the most affected skilled women are young, 'there is real concern that this educated female workforce may never be able to complete their transition into satisfactory employment'. Moreover, the problem is a loss to the human capital of Palestine, because it excludes half of the potential highly skilled workforce from contributing to growth. Therefore, policy action is required to address this socio-economic situation and tackle the persistent constraints that keep women out of the labour force in Palestine. The available literature does list several concrete and actionable short- and longer-term policy recommendations to enhance female employment. They include working on gender-neutral labour legalisation, starting with prohibiting discrimination in the hiring process and removing administrative barriers to female employment (e.g. requiring the permission of a husband). From another angle, female employment can be facilitated through support structures such as dedicated transportation and childcare as well as gender-specific matching services to enhance women's entry into the workforce (especially in the private sector to balance their overrepresentation in public-sector jobs). Last but not least, from a longer-term perspective, social norms should be addressed through affirmative action to create women-friendly safe spaces in the workplace (e.g. codes of conduct against sexual harassment) and efforts to change public opinion on gender biases[73] WB 2018a p. vii-viii, 12, 43-46; WB 2019c p. 42.

.

2.5 The untapped human capital opportunity of continuing education

Employer surveys indicate that very few companies in Palestine provide in-company training for their employees, 'with fewer still acknowledging they have an allocated budget for human resource development. […] Only 22 percent of business owners report that their companies have a dedicated training and human resource development budget and policy'. Citing the World Bank, GIZ notes that the situation differs widely by region: '[o]nly about 3 percent of firms in Gaza offer formal training, compared with 14 percent in the West Bank and 9 percent in East Jerusalem'. A lack of incentives (e.g. tax incentives, training levy, etc.) to encourage employers to upskill, reskill or accredit their workforce is cited as the main reason[74] GIZ 2020 p1.

.

Nor do young graduates seem to find their own way into training centres or online training to enhance their employability through upskilling. A 2015 AWRAD & CARE study finds that 'the reluctance to seek outside training was caused by a variety of factors, including lack of knowledge, scepticism of quality and discrimination/nepotism in selection processes'. The Torino Process national report does refer to a number of pilot initiatives to boost continuing vocational education and training (CVET) either on a project basis (often supported by donor projects) or on a more permanent basis. The initiatives include courses targeted at vulnerable groups in remote areas (NGO-VET institutes), courses for female-headed households, courses for unemployed youth, etc.[75] AWRAD & CARE 2015 p.8, 51; NR 2020 p44-46.

Overall, limited information is available on upskilling and more broadly on adult training or lifelong learning in Palestine. A recent survey by DVV International, which focused on adult education, has noted how disjointed this area of HCD is in Palestine. Programmes are offered by a multitude of providers, ranging from 'institutions affiliated to the Palestinian ministries within the programmes offered by the directorates of these ministries in the various Palestinian governorates, to centres affiliated to these ministries such as the Ministries of Labour and Social Development, to programmes offered by relevant departments such as literacy programmes offered by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education within the framework of its directorates in the various governorates and administrative regions'. In addition, Palestinian universities provide continuing education through their Continuing Education Centres, private training providers offer a variety of courses (of varying appeal and licensed under different ministries), cultural or educational centres provide languages and related courses, UNRWA provides VET training to refugee youth through a number of its centres, and last but not least civil society organisations[76] ”During the first two decades of the life of the Palestinian Authority, this category of institutions has received considerable support and funding from international institutions, making it a key player in adult education within this department.“ DVV 2019 p.68.

provide a set of courses on life skills, leadership skills, organisational work and personal development[77] In an attempt to categorize continuous education in Palestine the DVV study mapped it out in three categories, namely a) in the field of literacy (a prerogative of the Ministry of Education); b) in the field of VET, including upskilling and reskilling, through courses related to the labour market (offered by all actors in continuous education); and c) in the field of community education with topics ranging from civic education to life skills and self-care (mainly provided by civil society organizations). (DVV 2019 p.67-71)

.

Continuing education is an important but often overlooked part of human capital development in Palestine. While there is a wide training offer available from many different providers, it is neither rooted in a broader vision of lifelong learning, nor based on a systematic analysis of training needs. Moreover, it lacks any structured link to the world of work.