This chapter addresses two human capital development challenges in more detail. For each challenge, the main problem is described in its societal context. Then the policy response is addressed and a set of recommendations put forward. As a result, the aim of the chapter is not solely to describe the issue but also to support policy reform for the benefit of making the best use of human capital.

Policies for human capital development in Palestine

Kelias

- Pirmas

- Publications & resources

- Publications

- Torino Process reports

- Current: Policies for human capital development in Palestine

An ETF Torino Process assessment

3.1.1 The issue

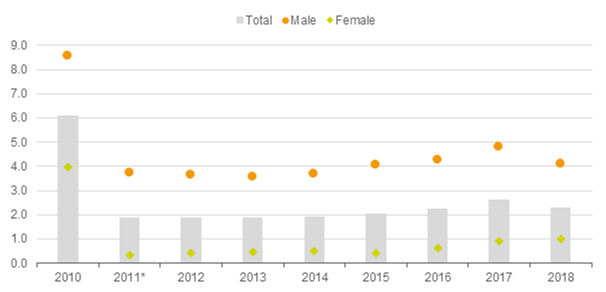

The share of students in initial VET in Palestine has long been considered marginal. For many years, the VET enrolment figures, which include only the number of students enrolled in the 11th grade of the formal secondary vocational education (industrial, agricultural, hotels, household economy), have hovered around 2% to 3% (excluding the commercial stream)[78] Since 2011 the commercial stream has not been included in the VET statistics, explaining a drop in VET students between 2010 and 2011.

. The latest available figures for 2018 point to a share of 2.3% of students in formal initial VET and find a sharp gender divide (4.1% for boys and merely 1% for girls). Between 2011 and 2014 the figures even dropped below 2%[79] MOEHE 2017 p87-88.

.

FIGURE 12. STUDENTS IN VOCATIONAL PROGRAMMES (% OF TOTAL UPPER SECONDARY STUDENTS ISCED LEVEL 3), 2000–2018

Source: UIS–UNESCO

*2011 break in time series: data do not include commercial schools

In the most recent Torino Process national self-assessment, the share of VET students has been investigated in detail and recalculated. As a result, the share has risen to include roughly 15% of students in the upper-secondary age cohort (aged 16–18)[80] A precise figure was not provided by the national report by lack of a national collection of VET data. The figure had to be calculated collating various datasets. Data on Continuous vocational education and training (CVET) is even more scarce, hence no figures are presented.

. This is obviously a positive trend and raises the figure to a more common level for the region, though it needs to be broken down and further analysed. The 15% figure includes the age cohort's enrolment in all forms of formal and non-formal VET training programmes provided by different ministries (except for the commercial stream, which has been excluded from VET since 2011). Across the board, enrolment figures are positive for each of the VET tracks. This is a result of the efforts made by various VET providers over the past few years to diversify their training offer in order to boost enrolment in VET. According to the national report, vocational education is up 56% between 2017–2018 and 2019–2020, vocational training is up 33% over the same period (including a doubling of people enrolled in evening courses at VTCs administered by the MoL), and technical education also rose between 2016 and 2018, despite a recent minor drop from 2018–2019 to 2019–2020. Lastly, there has been an encouraging reduction in gender disparity over the past few years[81] NR 2020, p14-17.

.

The national report lists the following main drivers of increased enrolment in VET:

- The MoE has provided three tracks for vocational education (Injaz, Kafa'a and apprenticeship), which together give students an opportunity to achieve according to their abilities and interests, and it has also increased apprenticeship provision[82] In a 2019 report, UNESCO explains the novelty and attraction of these three expanded tracks in vocational education as follows:

- “Graduates of General (high school) Examination; (INJAZ) for all professional branches,

- Professional Proficiency: applied for the first time in the academic year 2018/2019 and aims to promote leadership and discover the talents and creativity of students. The student with a certificate of PP goes directly to the labour market, and can join the technical colleges in the same specialization

- Apprenticeship: Students are trained in the labour market for two days a week and pursue their studies in their vocational schools for three days a week. The apprenticeship system aims at preparing the vocational student to enter the labour market after graduation.” (UNESCO 2019 p. 13.)

. - The MoE has introduced 39 vocational units in general education schools to ensure access to vocational education in all geographical areas.

- The MoL has created new centres and increased the number of provided vocations.

- Non-governmental centres have also increased their centres and vocations.

- New specialties and new centres have opened in the government, NGO VET and private sectors.

- Several agreements have been signed with donors such as GIZ to finance the development of training programmes and enhance infrastructure (e.g. buildings, equipment and furniture).

- There is now optimal use of institutions and resources, which are operating at maximum capacity after adding ongoing evening courses in addition to morning courses by the MoL and some NGOs.

- There is now optimal use of resources through the use of different TVET institutes by others, such as the agreement signed between the MoL and MoSD to use centres and resources[83] NR 2020 p.43.

.

Beyond the rise in enrolment figures, there have also been changes of a more structural nature. There has been a long-standing discussion on whether to consider the commercial stream as VET or not, with considerable effect on the VET share of students. This led to a significant reduction in 2011, when the commercial stream was taken out of the VET cohort. Nowadays, the barrier between the VET and general education subsystems is being challenged and has been pulled down de facto with the roll-out of vocational units and a technology track in general education. In higher education, some universities now also provide technical education, courses have increasingly been developed in cooperation with industry (e.g. through donor-funded pilot schemes for dual studies), and the creation of a VET university is under development.

In keeping with international developments, short-term, modular courses have been developed in line with industry needs and some VET schools have opened up in the evenings to facilitate continuing training through CVET courses. The expansion of the number of VET educational tracks described above has resulted in a proliferation of training programmes. Overall, the new programmes have been developed (often with donor support) on the basis of a proper labour market and training needs analysis. The identified skills have been translated into increasingly flexible, modular, competence-based curricula that include soft skills and work-based learning components and rely on the broadly agreed-upon Palestinian Occupational Classification (POC) and/or Arab Occupational Classification (AOC).

Such an expansion and diversification of VET provision is reassuring in terms of increased enrolment, but it also exacerbates the existing fragmentation of VET training supply and the dramatic lack of overarching governance. As a result, the new training modalities under various educational tracks offered by different providers pose a risk of completely losing oversight, let alone having a common standard for quality assurance. As for objectives and performance indicators, each ministry continues to use its own in the absence of a common framework. Since VET does not have a common system for accreditation and quality assurance, fragmentation is the norm and there is a risk of duplication, lack of recognition and limited vertical mobility. The scope of the Accreditation and Quality Assurance Committee (AQAC) is limited only to higher education. Its duty is to license higher education institutions (including technical colleges) and accredit the qualifications for their training programmes. Currently, the accreditation and licensing of other VET institutions and the adoption of their programmes take place according to rules set by the bodies responsible for each system. The absence of any agreed-upon, functioning National Qualifications Framework (NQF) further hampers the linking of certificates from VET training to a nationally agreed human capital development (HCD) framework[84] NR 2020, p.10, 62-63.

.

Priorities and effectiveness

The debate surrounding a comprehensive governance structure for VET in Palestine is over two decades old. It was originally addressed in the Palestinian TVET National Strategy (1999), followed by a structure set out in the revised TVET Strategy (2010). For most of that time a broad consensus existed in relation to the importance of comprehensive governance and its main lines. According to GIZ, '[a]s a matter of fact, most reports since 2010 describe optimistically varying setups of a TVET governance that have never been realised (so far)'. Over the same period, many stakeholder meetings have been convened and 'policies and regulations have been drafted, specific measures and lots of activities implemented, but almost none […] found their way into the living reality of TVET in Palestine'[85] GIZ 2020 p9-10.

.

Nevertheless, elements of policy work that are now surfacing could eventually converge into a common vision for VET, crossing the barriers between education subsectors and stitching together a horizontally and vertically permeable training system. Examples include the formalisation of private training through the licensing of for-profit private training centres, which is currently the prerogative of the Ministry of Labour as stipulated under Labour Law No. 7 of 2000 Chapter Two Article 22[86] NR 2020, p.8.

, and the harmonisation of TVET and higher education with the needs of Palestinian development and the labour market through the endorsement of a 'policy paper on integrated education in institutions of higher education prepared by a committee in accordance with the Cabinet Resolution No. 04/139/17 dated 14 February 2017'[87] UNESCO 2019 p13.

.

Shortcomings and policy gaps

Arguably, it is precisely the lack of a superstructure that prevents the mentioned achievements from turning into genuine policy change around VET. According to the national report: '[d]espite the existence of the Palestinian Labour Law of 2000, the Law of General Education of 2017 and the Higher Education Law of 2017 and the provision of some articles therein, this legislation in its entirety does not contain sufficient tools for the development of the TVET system in all its aspects. Legislation is still needed to regulate VET in general'. A governance model was finally initiated in 2016 under the guidance of a TVET Higher Council with a technical arm dubbed the Palestinian Development Centre for TVET. However, the governance structure lasted only two years and ultimately 'a ministerial committee was formed to formulate a vision for developing TVET, by the Cabinet decision dated 13 May 2019'. The expectations for the ministerial committee are high, namely to overcome past failures so 'that [it] enables setting the needed policies for a unified system, providing leadership and enabling implementation of TVET system strategies, and hence providing the Palestinian TVET model'[88] NR 2020, p.10-13.

. As a result, the end of 2020 appears yet again to be an important moment for VET in Palestine, with the newly revised Labour Sector Strategy 2020–2022 establishing the increased effectiveness and relevance of the TVET system as one of its main objectives. Last but not least, the Cabinet has approved the law establishing the new TVET commission, which now awaits countersignature by the President.

The Cabinet decision of 2020 to revamp the overall governance model of TVET and set up a TVET commission is reassuring. It could lead to a long-overdue solution that proves sustainable for the unified, coordinated provision of technical and vocational training. Many improvements in access, quality and linkage to the labour market are at risk of fading, however, if the issue of fragmentation is not solved in the foreseeable future. The recommendations in earlier versions of the TVET strategy (dating back to 1999 and reconfirmed in 2010) remain relevant and significant efforts are needed to systematically address strategic elements indicated by MAS in 2015, such as system empowerment, TVET offerings, improved quality training delivery and ownership[89] MAS 2015 p4; NR 2020 p65.

.

Though VET governance is now an urgent priority in its own right, it may also be possible to seize the momentum by enlarging the scope of the coordination efforts to capture other initiatives that happen either at the margins of VET or in parallel. The education landscape is changing and the barriers between VET, CVET, technology training, etc. are fading away. The momentum created by reviewing the VET governance model in Palestine is a unique opportunity to consider new societal needs through a comprehensive structure for human capital development on one hand and more individual learning pathways on the other hand.

Focus on lifelong learning guidance of talent rather than institutions when developing a comprehensive HCD framework.

Lifelong learning is already a reality in people's lives, but more is yet to come. While current levels of CVET and LLL are low in Palestine, it can be expected that Palestinians, as in other countries, will increasingly have to engage in learning throughout their lives in order to keep their skill set up to date. In a recent report the European Commission states that 'individuals now experience numerous transitions throughout their lives, as occupations change, occupational prospects are less clear and career pathways have become more diverse'. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 aims to 'ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all'. Such a lifelong perspective provides a more fluid and comprehensive perspective for providing guidance and relevant training to young people and adults of all ages and for supporting reskilling and upskilling.

In the short term, it will be key to shift the focus to the individual in order to provide guidance and relevant training throughout life. Such a shift to the individual allows for talent management that fosters the key competences necessary in a 21st century economy, including adaptability, creativity, self-management, etc.[90] In its recommendation of 2018, the European Council states that “nowadays, competence requirements have changed with more jobs being subject to automation, technologies playing a bigger role in all areas of work and life, and entrepreneurial, social and civic competences becoming more relevant in order to ensure resilience and ability to adapt to change. (EC 2018a p.1). While in its report 'New Vision for Education: Fostering Social and Emotional Learning through Technology', the World Economic Forum in 2016 further deepened the notion of 21st century skills around Social and Emotional Learning that prepares students to be more versatile and agile for evolving workplaces. (WEF 2016)

It also allows for a more tailor-made inclusion of vulnerable groups. With the majority of young Palestinians struggling to find a meaningful pathway into the 21st century economy, urgent action is required. This starts with scaling up reskilling and upskilling programmes that help Palestinian youth to develop additional skills and competences in order to enable them to integrate better into the economies of Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem. For a large contingent of unemployed university graduates, this might mean acquiring technical skills.

As the boundaries blur, it will be hard to continue organising learning through isolated subsystem silos (formal, non-formal, on-the-job, etc.). The 2018 European Council recommendation puts it as follows: learning systems will have to become more comprehensive to ensure a seamless pathway 'to develop quality early childhood education and care, to further enhance school education and ensure excellent teaching, to provide upskilling pathways to low-skilled adults as well as to further develop initial and continuing vocational education and training and modernise higher education'[91] EC 2018, p. 3

. In its new Skills Agenda, the EU puts a strong focus on the creation of a real lifelong learning environment[92] EC 2020b, p. 4

. Individual learning trajectories are increasingly becoming the focal point for learning systems in many countries. The pioneering of One-Stop Shops in Finland is often cited as a best practice for putting the learner at the centre without discriminating by age, but other examples include individual training accounts ('compte personnel de formation') in France and career vouchers ('loopbaancheques') in Flanders (Belgium), which both facilitate lifelong learning journeys that put career development at their core[93] EC 2020a, pp. 49–54

.

In the medium term, a shift in mind-set is also needed in Palestine. Instead of reforms that focus on enhancing coordination between VET and the existing subsystems of training providers, efforts should be made to address the governance of HCD in a more fluid and comprehensive framework from the lifelong career perspective of learners[94] In a 2015 study, AWRAD & CARE surveyed VET graduates and found that 'a majority of graduates say they received no career counselling in the course of their education, and only half of educational institutions believe they have such offices' (AWRAD & CARE 2015, p. 8).

.

In the long run, letting go of supply-driven training provision and putting the individual at the core of lifelong learning and lifelong guidance will require the orchestration of a comprehensive HCD governance model. As the European Commission notes, '[i]n an ideal situation, actors would work in cooperation and coordinate services with the aim of providing a seamless service across an individual's life course'[95] EC 2020a, p. 49

. Such an overhaul of the HCD system modelled around individual learning pathways (e.g. individual learning accounts) will inevitably require a meta-level review of Palestinian learning subsystems, taking into account initial pre-employment training as well as social issues and economic requirements.

Rebalance the discussion around (long overdue) enhanced coordination and comprehensive governance of VET to capture a wider scope of HCD.

The importance of comprehensive VET governance still stands, but in 2020 there are additional elements that can no longer be ignored in this debate:

- The national report describes in detail the cracks in what is currently considered part of the VET subsystem, which is scattered across a number of ministries (MoE, MoHE, MoL, MoSD, etc.), subject to various laws and regulations, and provides training that results in a variety of certifications.

- The creative and successful expansion of VET into general education shows that the barriers between different educational tracks have become more artificial and that their overlap is increasing, well beyond the long-standing discussion over whether to consider the commercial stream as VET. This also brings to light the blind spots in the fragmented system. TVET units within general education suffer from a lack of technical content and training capacity[96] As a recent unpublished GIZ analysis puts it, 'the teachers recruited for the TVET exposure by the Ministry of Education were obviously mostly trained Arabic, Literature or Science teachers with no TVET background. Some training measures to qualify these teachers were already implemented, but this still bears the risk that the idea of a TVET exposure to attract students is being implemented in an unrealistic or even demotivating manner' (GIZ 2020, p. 4).

, while at the same time the VET track itself would benefit from ongoing reforms towards student-centred learning and digitalisation. The difficulties surrounding the positioning of the short-lived 'technology stream'[97] The technology stream was briefly initiated in the education system, but it was recently stopped prematurely.

are another example of the artificiality of the divide. - A number of pilot projects promoting CVET have started to bear fruit with a series of VET schools and centres that open up in the evening. Beyond the benefits for learners, they hold great potential for repositioning VET providers in terms of upskilling and reskilling the workforce and indirectly enhancing the reputation of VET in general. Despite the positive trends, such as increasing numbers, the joint development of courses with industry, and the fact that partial qualification can now be achieved, an overall vision for CVET is lacking. The risk is that a parallel system will be put in place instead of a more integrated lifelong learning policy for all.

Where earlier recommendations have focused on overcoming the divide between formal and non-formal training within the TVET subsector, the scope of the new review calls for a fresh start. In the short term, ETF recommends making a fresh effort to reassess the scope of comprehensive governance for the VET ecosystem.

In the medium term, continuing education merits more attention as a full branch of a mature HCD system in order to confront the key issues described by DVV, namely that the challenge of 'any strategic planning for the development of adult education lies in the absence of a unified understanding of the subject of adult education, and in the extreme weakness of an organised database that reflects the reality of this education in relation to institutions'[98] DVV 2019, pp. 77, 78

. In a first effort, it will be of utmost importance to review the national strategy on continuing education by 'drawing on the experience of work during the past years of the plan's life and developing an executive plan for this strategy'.

Finally, in the long run, the review of a strategic framework for VET or for continuing education should be carried out not in isolation but from a broader HCD perspective. This is in order to close the loopholes in the system, ensure a seamless coordination between the various education systems, and ultimately provide a comprehensive service to the whole population (from young to old). Even as the relevant authorities proceed with the implementation of the national TVET Commission to improve the VET ecosystem, the reasoning of the DVV study remains valid when it flags the need for a dedicated higher national authority for adult education in Palestine to spearhead continuing education with social policy in mind. Come what may, a thorough coordination and integration effort will be necessary to bring together the multitude of providers and programmes in the various HCD subsystems. Ultimately, it is up for debate how best to unify the approaches in Palestine and implement a comprehensive training system from a lifelong learning perspective.

Prepare the ground for a flexible HCD system by urgently finalising a National Qualifications Framework (NQF).

All strategic reviews of the VET system in the past two decades single out the lack of a common qualifications structure as a major gap. The national report (2020) is clear: 'VET needs a comprehensive system of accreditation, quality assurance, and accompanying systems that have been mentioned in the proposed strategy and the proposed law. The system should include clarification of standards, structure and reference. As a start, Vocational Training needs a qualification and accreditation system for the skilled and limited-skill worker levels, and to accredit prior learning and acquired skills through experience'[99] NR 2020, p. 62

.

The reinterpretation of the VET subsector within a wider approach to human capital development, as described above, also means that its rethinking should involve the legal establishment of the entire education sector as one integral component. As MAS has indicated, 'this goal can only be achieved if existing education and training laws are somehow integrated to meet that vision. To that extent, it has become of utmost importance to acknowledge and endorse at the national level a progression route to all kinds of education which necessitate TVET skill levels. Accordingly, certifications will need to be nationally acknowledged within the current education system. This will certainly change the negative perception of TVET within Palestinian society as a dead-end type of education'[100] MAS 2015, p. 4

.

In the short term, begin rethinking the legal framework and references for the entire education sector.

In the medium term, the NQF should become the backbone of a comprehensive system. Although a broad consensus exists over the need for the NQF and it has been provided for in all earlier TVET strategies, it has not materialised in the past two decades. The issues of transparency and mobility are of key importance for qualifications systems, and the implementation of the NQF will require efforts that go well beyond the VET subsector. In its strategic plan 2017–2022, the Ministry of Education indicates that 'having a National Qualifications Framework (NQF) and the Palestinian Occupational Classification (POC) constitutes a major milestone in capturing previously unrecognised qualifications [and] offering much needed recognition and job opportunities for a large number of professionals'[101] MoEHE 2017, p. 87

. Though some degree of system integration has been achieved, the recognition of qualifications and certification is still divided between the various ministries involved and it is still limited to vocational education and technical education for some tracks[102] 'According to the approved reviewed TVET strategic plan (2010), the system assumes permeability between different levels. Accordingly, different measures were adopted recently which include accepting the enrolment of vocational education graduates in all specialisations at universities (with the exception of the medical specialisation), whereas previously they were accepted only in fields relevant to their studies. In addition to developing the occupational standards and curricula of a number of professions within the different levels according to the adopted AOC, vocational training (VT) is still in need of an accreditation and qualification system to link with the national education and training framework' (NR 2020, pp. 9–10).

, specifically where the Ministry of Labour still needs to develop its qualifications and accreditation for vocational training[103] NR 2020, pp. 39, 46

. Despite the limited progress, the national report (2020) remains hopeful: 'a draft NQF structure does exist but it needs to be updated and amended both for VET and for other levels. Upon its completion, one national framework should facilitate guaranteed permeability between initial VET, academic education, continuing VET and lifelong learning'[104] NR 2020, pp. 8–9

.

In the long run, the existence of an NQF would also be the conditio sine qua non for the lifelong career guidance mentioned above, because it would serve as the common point of reference to enable the validation and recognition of skills and qualifications acquired through non-formal or informal learning and act as a benchmark for developing individual flexible learning pathways for further training. Given the high prevalence of the informal economy in Palestine, the recognition of prior learning and the validation of informally acquired skills could play a significant role in the formalisation and upgrading of economic sectors. Hence the urgency, however difficult it may be, to take up the work of creating the NQF as a backbone for accreditation and certification.

Globally, the digital transformation of economies is considered to be both a threat to the job market and an opportunity to create new jobs, increase productivity and drive growth[105] WEF 2018

. In its 2019 report on jobs, the World Bank cites 'boosting technology-based services' as one of the key job creators for Palestine: '[g]iven the small size of the economy and the restrictions on physical trade, the best option to create more and better jobs […] is to boost tradable services, particularly those based on digital technologies, such as information and communication technology (ICT) services, whose global demand is rapidly growing'[106] WB 2019c, pp. 31–32

. Though the share of the ICT sector is only 3.2% of Palestine's GDP (PCBS, 2018), the expectations during the Torino Process debates in Palestine were high for the growth potential of the technology sector, which is flagged as a 'strategic force to achieve high rates of economic and social development'[107] NR 2020, p. 31

.

Growth potential of the sector

In order to understand the potential of the Palestinian technology sector as a job generator, a more detailed breakdown of the sector is needed. In general, the sector is understood to include data-based and technology-enabled services, such as ICT and business services. Online freelancing is a growing business not only globally but also in Palestine, which has seen an increase in online freelancers (especially in Gaza), in terms both of individuals and of small outsourcing companies that service other countries (mostly in the Arab world). Exact numbers are difficult to obtain. UNDP sees the number of freelancers varying according to the portal, and puts the range at between 2 000 and 7 000[108] 'For example, there are some 3 000 Palestinian freelancers to be found at freelancer.com, and around 2 000 more are registered on Upwork.com. Approximately 7 000 Palestinian freelancers are registered on the Arab-world-based portal Mostaql.com.' Accessed at https://www.ps.undp.org/content/papp/en/home/presscenter/articles/2018/freelancing-in-the-state-of-palestine.html on 19 June 2020

. Freelancers now provide a host of digital and administrative and support services (including accounting, marketing, event organising, data entry, design, programming, etc.)[109] BTC 2016, p. 2; WB 2019c, pp. 31–33

.

A better understanding of the trend should allow the Palestinian economy to reap the fruits of digital transformation and play a part in the global value chains of Industry 4.0, to the extent possible. Online freelancing is often cited as a subsector with great potential for Palestinian youth to enter the platform economy, particularly in Gaza. In this respect, the World Bank identifies a global trend (that also exists to a lesser extent in the Arab world) where '[d]igital technologies have enabled large projects awarded to firms in some part of the world to be broken down into small parts and tasks, which are outsourced to firms and individuals in other parts of the world. Tasks can be complex (e.g. software development, graphic design, media production, content development, website design, e-marketing, translation) or simple (e.g. labelling photos or videos, describing products, data gathering, answering calls), providing opportunities for high-skill and low-skill youth alike'[110] WB 2019c, p. 33

. A labour market needs assessment that was conducted by the Belgian Development Agency in 2016 using an employability matrix points to two pillars of Gaza's competitive edge in the sector, namely: '(i) the outsourcing business model that is increasingly being recognised as a long-term competitive strategy for business success owing to lower infrastructure investment, enhanced focus on unique business core functions and overcoming seasonal workload that does not require employing new staff; and (ii) the backbone for these services is highly linked and dependent on technology advancement with noted focus on ICT development'[111] BTC 2016, p. 2

.

Between a 'nascent' and an 'advancing' start-up ecosystem

Palestine is home to a small but growing start-up ecosystem. Certainly, the growth-focused world of start-ups might have an overall positive impact on the economy and society, but its net value contribution to the economy and job creation is more ambiguous. In a recent report, the World Bank investigates the tech start-up scene in the West Bank and Gaza. In terms of growth rate over the period 2009–2015, the World Bank calculates that 'on average, each year 19 more start-ups are created than in the previous year, resulting in a 34 percent compounded growth rate in start-up creation [and] about two-thirds of the start-ups surveyed reported hiring at least one employee, with a median of three jobs per start-up'. This leads to the calculation that over the same period, 1 247 jobs were created in the ecosystem. This is a small number in comparison to the high expectations of the technology sector in terms of job creation[112] World Bank 2018b, pp. 3–9

.

To understand the maturity of the ecosystem and identify its main drivers, several hundred Palestinian entrepreneurs were interviewed in a Global Entrepreneurship Research Network survey between 2016 and 2017[113] 'For this analysis, 423 entrepreneurs were surveyed in the West Bank and Gaza between December 2016 and February 2017 and relevant data were collected on 142 start-ups and 196 start-up founders.' Although it is one of the largest survey samples of start-ups ever seen in Palestine, the 'data set is not exhaustive and only represents a subset of the ecosystem's start-ups. Moreover, it is subject to survivorship bias and does not include start-ups that were no longer in business' (WB 2018b, pp. 2, 3, 29).

. Based on the survey results, the World Bank puts the Palestinian ecosystem between the 'nascent' and 'advancing' stages. Whereas the community of stakeholders and access to financing are judged to be at a more advanced level, the skills and supporting infrastructure are still at a nascent stage[114] World Bank 2018b, pp. 3–9

.

Despite some obvious constraints (such as limited infrastructure), there seems to be a fairly conducive enabling environment for a tech start-up ecosystem in Palestine. The availability of finance and facilitation is surely seen as a driver. So is the interconnectedness of the ecosystem. In the specific case of a highly fragmented society that is subject to physical separation and movement restrictions, the Palestinian start-up ecosystem is obviously fragmented. The World Bank finds it clustering around two main poles: Gaza Sky Geeks in Gaza and Birzeit University in the West Bank[115] East Jerusalem is not considered as a separate entity in the World Bank study. While it is more closely connected to the West Bank, it is also subject to other administrative and financial frameworks imposed by Israel.

. Despite its mobility constraints, the Palestinian ecosystem is regarded as 'highly connected to international actors, connecting to extensive networks of knowledge from clusters outside of the West Bank and Gaza'[116] 'These international actors are both regional (MENA region) and international (primarily US actors), including many university networks […] which suggests that there is a large proportion of the start-up ecosystem with foreign experience or that floats between the West Bank and Gaza and another international residence' (WB tech 2018, p. 20).

.

The extent of these networks could be reassuring for the start-up scene, since the survival chances of a start-up are often measured by its connectivity and its ability to interact with the surrounding ecosystem or network of stakeholders. A recent article in Nature goes even farther, testing the hypothesis that start-up networks have predictive power and using network centrality as a point of reference. The article poses a theory that 'the position of a start-up within its ecosystem is relevant for its future success' and 'the network of professional relationships among start-ups can unlock the long-term potential[117] 'For instance, skilled employees moving across firms in search of novel opportunities can bring with them know-how on cutting-edge technologies; advisors who gained experience in one firm can help identify the most effective strategies in another, while well-connected investors, lenders and board members can rely on the knowledge gained in one firm to tap business and funding opportunities in another' (Nature 2020, p. 1).

of risky ventures whose economic net present value would otherwise be difficult to measure'. More research would be needed to identify the specificities of this international exposure (e.g. any links to the Palestinian diaspora) or its potential for cross-border economic development and its eventual influence on job creation[118] Nature 2020, pp. 1, 4

.

Traditional skills

Referring to recent international literature, the World Bank argues that beyond the start-up entrepreneurial ecosystem, 'new technologies also generate new job opportunities for workers with skills that complement technology, including cognitive and socio-emotional skills. Recent work shows that countries that invest more in these skills and ensure a supportive environment for firms to do business, innovate, and adopt new technology stand to gain the most from technological changes, while those who do not [do so] risk falling behind'[119] WB 2019c, p. 31

.

In theory, Palestine with its overall high educational attainment should be well positioned to reap the fruits of the booming technology sector. Its highly skilled youth are often cited as one of the main drivers of technology-driven growth. The question, however, is whether Palestine is investing in the provision of the right skill set. From the above example of the start-up ecosystem, the answer seems to be no as skills are not necessarily seen as a key driver. According to the World Bank, '[e]ducation is especially high among founders in the West Bank and Gaza, with over 55 percent having a university degree, and over 19 percent with graduate degrees (masters, professional or doctorate). […] [T]he majority of founders (52 percent) have a degree in science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM), 21 percent have a degree in business, and 11 percent have both STEM and business degrees'. However, the skill set of entrepreneurs (founders and team members) are found to be too traditional and lack both creativity and due financial capacity. As a result, for many investors, skills are considered a drawback[120] WB 2018b, pp. 12–14

.

Similar skills gaps seem to exist for other technology-based services, impeding their ability to expand. For the platform economy to flourish, certain preconditions need to be met. As a result, limited skills training and a lack of mentorship opportunities are flagged as among the main constraints for the development of the technology sector as a whole. For the tech sector's potential to be fulfilled, the Solutions for Youth Employment report of the World Bank warns that certain preconditions are required. Countries should 'overcome economic, social and institutional barriers' and invest in order to 'alter their education and training systems to provide the more advanced technical and soft skills needed, and rewarded, by the new economy. This will be particularly important for youth entering the labour market for the first time'[121] WB 2019c, p. 33; S4YE 2018, p. 8

.

Connection to VET

Expanding the scope beyond the tech service sector and assessing the extent of the advances in digital technology that are transforming other sectors, the stakeholders of the national Torino Process also raise caution by stating that 'the digital transformation contributes to skill mismatch'. Further skills anticipation will be required to understand the changing needs arising from digital transformation processes. To understand the needs, however, labour market analysis processes will require revamping and more collaboration with private-sector actors will be needed to accommodate any changes in industrial processes. As a result, the Torino Process national report indicates that the 'VET ability to meet technology skills mismatch is affected by methods of identification of new vocations and curricula development that have limited labour market contribution and [are] in many cases led by the government'[122] NR 2020, p. 36

.

On the training provision side, a full-scale review and relevance check will be required. This is the case not only for general education, but also for VET. It is not clear to what extent the profiles that the Palestinian VET system currently delivers at the semi-skilled level are still relevant and sufficient for the technology sector or the automation process of the digital transformation across sectors. One key will be to understand whether the initiatives to diversify VET provision (as described under HCD issue 1) can provide the required skill set, including the necessary foundational skills (problem-solving, creativity, etc.), entrepreneurial learning, and flexible initial and continuing VET adapted to sectors disrupted by digital transformation.

Priorities and effectiveness

In the problem statement of the recent STEM strategy, the Ministry of Education makes the case for 'a qualitative shift in the teaching and learning process in Palestinian schools […] thereby improving human capital in order to meet the current and future needs of society in the knowledge economy and the labour market'. The strategy evokes a sense of urgency to 'solve problems of economic development, such as low employment rates, unemployment and poverty among young people, as well as the huge gap between rich and poor, as it is concerned with providing the labour market with qualified high-tech workers'. Though focused on teaching STEM subjects only in general education, the proposed pedagogical approach also addresses broader issues such as: a) integrating scientific method into daily life; b) transversal implementation of 21st century skills in the curriculum, including logical thinking, decision-making, teamwork, etc.; c) a multidisciplinary approach recognising the strong link between STEM education and the arts that promote design, creativity and innovation; and d) organising the learning around experience-based activities through discovery, investigation, manual activities, etc. The level of implementation of the strategy is to be further investigated as is its ability to disrupt the previously mentioned traditional learning culture[123] MOE 2019, pp. 2–11

.

In addition, the Covid-19 outbreak has pushed the relevant ministries, schools, teachers and students to move ahead with digitalising the learning experience. In this respect, several efforts have been made in cooperation with different partners, including the provision of electronic learning platforms by the MoE (https://i2.elearn.edu.ps/), the development of an e-learning manual led by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, and the delivery of online short courses in solar energy and hybrid automotive technology by the MoL in cooperation with the local chambers of commerce[124] ETF 2020b, pp. 61–63; ETF 2021, p. 3

.

Shortcomings and policy gaps

In 2016, a technology stream was launched as a track in general education. The stream rapidly managed to attract close to 4 700 students in 170 schools. The stream was deliberately set up outside the VET track as a positive career choice for students with ambitions in the technology sector. Despite its success, the stream was short-lived and taken out of the Palestinian curriculum in 2019. A lack of clarity on where to position its qualification has been cited as one of the main reasons for its removal from the educational calendar. It fell into the cracks, so to speak, between general education and VET.

Without neglecting the importance of ongoing VET reforms in Palestine, a 2018 concept paper by the TVET Department of the Ministry of Education (and Higher Education), which describes the way forward, makes no reference to the technology of digital transformation. It focuses solely on improving VET quality, governance and enrolment figures. Its merits in terms of increased enrolment have been discussed under HCD issue 2, as have its breaking down of barriers between VET and general and higher education.

The abovementioned STEM strategic plan (though currently limited only to STEM courses) would actually constitute a golden opportunity to review and future-proof the Palestinian curriculum for all educational tracks, including VET. The plan already makes explicit reference to coding, electricity and digital electronics. Other subjects, such as mechanics and transport technology, design, and electronic design, to name but a few examples, have a clear overlap with VET in a 21st century setting. With the digital transformation gradually making its way into all sectors and all skills levels, it would be paramount to enlarge the perspective of the strategic plan to cover the education system more broadly. The strategy mentions the formation of a national team for the gradual adjustment of the curriculum and raises collaboration with higher education. However, VET is not mentioned in the strategy nor is there any description of divergent educational pathways that would lead to VET either at secondary-school age or at tertiary level.

The digital transformation of the global economy comes with both challenges and opportunities. As described above, many sources agree that the Palestinian technology sector has the potential to play a key role in economic development and job creation. Currently, however, skills are seen more as an impediment than as an enabler. With human capital as its main resource, the Palestinian economy has no option but to seize the opportunity. In addition to other required policy changes to improve the business climate (e.g. the reduction of red tape)[125] In terms of infrastructure or the enabling environment, Palestine obviously has a number of constraints that hamper its ability to promote technology-based services as one of its key job creators. While some of the constraints lie beyond the control of the authorities ('3G mobile networks were only introduced in 2018 (in the West Bank) and suffer from insufficient mobile spectrum'), other conditions could be enhanced (e.g., the lack of a secure online payment platform). According to the World Bank, 'it also requires institutional and regulatory reform to improve competition and oversight in the telecom industry'. Also, in terms of business environment, nothing less than a Big Bang regulatory reform will be needed to remove cumbersome business regulations. This is the case for all businesses (see HCD issue 1), but particular attention should be paid to enhancing the digital economy (WB 2019c, pp. 31–32, 37).

, a review of the skill set of Palestinians could contribute significantly to Palestine's participation in a global digital value chain.

Maximise the potential of technology-based services as a job generator by revamping training provision.

In the short term, the education system should review the relevance of various educational tracks both to provide the adequate skill set needed to enhance the Palestinian contribution to a technology value chain and to allow for skills to become a main driver within the Palestinian tech ecosystem and boost technology-driven services. Such a review should be based on a thorough skills anticipation or occupational analysis of the sector (see recommendation b) and will inevitably result in a set of new and adapted profiles at various occupational levels. The education system's response to provide the respective qualifications cannot be limited to a single educational track, because the skills and competences required by the technology sector are spread over various levels. Rather, the response of the Palestinian education system should build on previous policy work around STEM in general education, the hybrid pilot of the technology track (which fell between the cracks of VET and general education), and incubation pilots and reinforced collaboration with industry in the realm of higher education.

In addition, the VET track (including at the lower skills level) should give attention to the pilot experiences of non-formal learning in boot camps (not only for coding but also for entrepreneurial education and life skills), because 'they have proven successful at rapidly assessing market gaps and demands in tech start-up ecosystems [and] can serve to include the low-educated population in the ecosystem by providing a basic set of skills connected to the ecosystem demand'[126] World Bank 2018b, p. 26

. Where the VET system is too traditional, it could benefit from the experience of the STE(A)M (science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics) tracks in general education with their focus on 21st century skills, such as creativity, problem-solving and teamwork, to bring innovation and initiative into the practical courses of VET. Actors such as Al Nayzak[127] https://www.alnayzak.org/

have been focusing on sparking innovation and creativity in Palestine through the organisation of fairs, innovation or maker spaces, and fabrication labs or fab labs. While these initiatives belong to the non-formal sphere, formal education (not least in VET) would benefit from the experiences to update its training offer. Also, the incubator mentoring method for start-ups, which includes access to start-up capital and guided practical entrepreneurship training, has strengths that could be applied to a low-tech incubation stream for a variety of VET profiles. Formal education should look into capitalising on best practices and mainstreaming key competences (including entrepreneurial and digital skills) as learning outcomes across various educational tracks, including VET. The Covid-19 crisis has shown the importance of developing digital skills among students and teaching staff, and steps have been taken in this direction.

In the medium term, a pragmatic focus is required to update training provision continuously to enhance the relevance of education for a technology-driven value chain in close cooperation with the private sector. It will be key to go beyond the divide between various educational tracks and look into cross-fertilisation between VET; the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM, or better yet STEAM, where the A stands for arts) provision[128] In the STEM Education Guide, the difference is explained as follows: '[t]he new element being championed today is arts. Those in favour of STEAM recognise the ability of the arts to expand the limits of STEM education and application'. This approach brings another core competence – creativity – to the table, which is included in the list of key competences needed for the 21st century. Accessed at http://stemeducationguide.com/stem-v-steam/ on 19 June 2020

in general education; and commercial and industry-oriented technology studies in higher education beyond the diploma level. The actors in the tech start-up ecosystem have high educational attainment, but their schooling is regarded as too traditional. In this respect, the experience of the VET stream in work-based learning can prove essential for the review of learning in other educational tracks. As the World Bank points out, it is crucial to '[e]xpand practical education in universities and through rapid skills training programmes and accelerators connected with public education programmes'. The general lack of financial literacy (identified as a major constraint by investors) can be addressed in a similar manner. Finally, to enhance the relevance of the training and 'address the shortage of quality mentors and strengthen support services', mentorship programmes need to be strengthened through the fostering of angel networks in order to professionalise accelerators, facilitate the entry of international talent (e.g. mentors, entrepreneurs or capacity builders) into the ecosystem, and enhance its interconnectedness[129] World Bank 2018b, pp. 4, 26

.

Finally, in the long run, it is worth considering investment in Level 5 certificates for engineering technicians. In countries where the digital transformation is disrupting the labour market[130] Including the Israeli economy

, engineering technician graduates with a (lower) Level 5 certificate are a sought-after niche group[131] The Skills Panorama for the EU Member States assesses the need for science and engineering technicians as follows: '[they] will probably be more sought after in the labour market. […] [T]his could be attributed to the increased need for high-level skills in the sectors employing both these occupational groups. […] In 2018, 53 percent of science and engineering professionals held a medium-level qualification. This is projected to fall to 45 percent in 2030. In contrast, the share of workers with a high-level qualification is expected to increase from 36 percent to 45 percent. The share of workers with a low level of qualification will remain more or less unchanged over the 2018–2030 period – moving from 11 percent to 10 percent'. Accessed at https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/analytical_highlights/science-engineering-technicians-skills-opportunities-and-challenges-2019

. In Palestine, graduate unemployment reigns among university alumni, including those from the engineering department. Similar to international demand, the creation of a more technical profile could also provide an opportunity for VET in Palestine. Discussions with a focus group from the technology sector held in East Jerusalem in early 2020[132] As part of an ongoing ETF study on the relevance of VET in East Jerusalem

indicate that the discontinuation of the more hybrid technology track in general education has left a vacuum that needs filling in the VET stream, either within the vocational education track or within technical education (diploma level). Not only might this be an opportunity to fill a niche in the global technology value chain (to be confirmed by more in-depth skills anticipation), but it could also contribute to raising the public image of a 21st century-oriented VET in Palestine.

Invest in real-time skills anticipation to assess the impact of digital transformation on all economic sectors to understand the new requirements in terms of HCD.

Digital transformation produces a skills mismatch that is not limited to the technology sector but to a large extent affects all economic sectors. Understanding the change in skills needs is key.

In the short term, investment is needed for more frequent skills anticipation exercises in Palestine, based on proven methods, such as surveying sector actors and using big data and other more creative methods, in order to capture the trends that are transforming sectors through the introduction of disruptive technologies or the reconfiguration of value chains as a result of technological advancements. These changes are exponential and increasingly the result of unpredictable factors[133] In 2020, ETF is working on new methods to explore how technological change and innovation – and other drivers of change – affect jobs and the demand for skills in specific sectors in its partner countries. Accessed at https://openspace.etf.europa.eu/pages/skills-future-country-studies-emerging-skills-demand-specific-economic-sectors

. Hence real-time information on skills demand should allow education and training to formulate an adequate response. Beyond initial training, it is crucially important to allow sectors to upskill and reskill employees to maintain or improve their relevant competences and boost productivity. As a result, digital transformation is inevitably a key driver towards lifelong learning systems (see HDC issue 1).

In the medium term, active labour market policies (ALMPs) should aim towards inclusion in order to ensure the increased participation of vulnerable groups in global value chains. In the case of Gaza, for example, this would translate into enhancing the participation of highly skilled women in the digital environment. Gaza Sky Geeks offers a best practice here: 'about half of the founders of the start-up companies mentored by Gaza Sky Geeks are women. In an effort to overcompensate for the current gap between males and females in the tech world, the goal is 80 percent. Moreover, the organisation has been supporting efforts to introduce young women to coding and web development skills, with the hope of integrating more women into the tech industry that has been growing rapidly in the Palestinian territories and providing job opportunities for them'. Upward trends in microwork and online freelancing in the platform economy create the conditions for, for instance, a large group of unemployed skilled women (in Gaza but also in other parts of Palestine) to gain access to global value chains from their home, giving them 'the flexibility they need to overcome social norms and barriers' that otherwise work to prevent them from accessing the labour market[134] WB 2018a, pp. xii–xiii and 41–42; WB 2019c, p. 43

.

Finally, in the long run, the focus of assessing the changes should go beyond the technology sector, because the digital transformation is expansive in scope. One key is to understand how the various tech ecosystems can work hand in hand with more traditional sectors and create tech verticals in order to expand innovation and creativity beyond the ICT sector, addressing niches in other sectors and entering traditional sectors including agriculture and crafts. Grounded in a solid understanding of global trends and the local labour market, the '[p]olicy actions can be applied to catalyse industry start-up innovation through open innovation and service co-development processes'[135] WB 2018b, p. 27

.