Kyrgyzstan faces a series of human capital development (HCD) challenges. The main HCD challenges identified from the information provided in the NRF are related to:

- increasing the county's income while combatting poverty

- the urban–rural divide and the resulting inequalities

- the prevalence of informal economy together with an unstable and unpredictable formal labour market

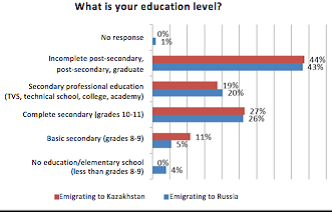

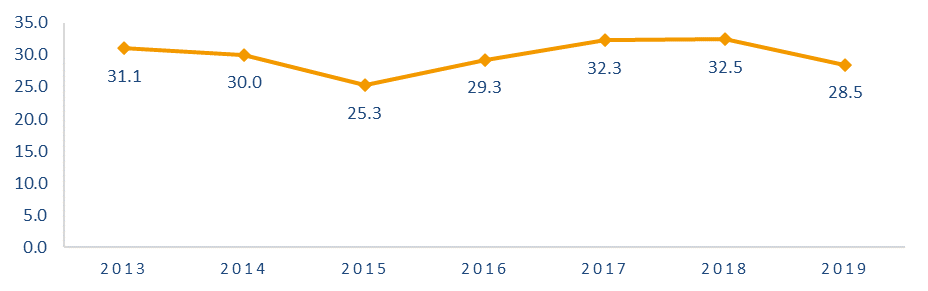

- the huge labour migration and related brain/skills drain, as well as a high dependency on remittances

- the government's ambitious digitalisation plan, which includes education and training

Most of these challenges point to a need to raise the level and quality of human capital in the country. While some features and trends in education and training point in a positive direction (e.g. better access to education for vulnerable groups, and increased funding for VET), others point in the opposite direction or even appear to have entered into a vicious circle. For example, the growing informal economy, serious problems in sustaining reforms, a lack of resources and capacities, the numerous obstacles to digital transformation, the continued low promotion and quality of VET, and the slow pace of structural change in training all offer little help towards achieving labour market relevance and overcoming underdeveloped social partnership and employer involvement in VET.

Many of these issues and challenges stand in contrast to the country's ambitious development goals and will require long-term efforts. Others call for immediate policy actions because Kyrgyzstan's younger generation in particular has high expectations of its government.