As elaborated in Chapter 2, it has become evident that human capital utilisation is an issue in Lebanon, and is related to the functioning of the labour market, indicating the need for a number of reforms to improve the responsiveness of the education and training system to its evolving needs. This chapter will discuss how the skills gaps and mismatch[42] Skills mismatch is an encompassing term which refers to various types of imbalances between the skills offered and the skills needed in the labour market

in the country are being addressed currently and how they could be further managed in the future, and how reinforcing shared governance and equipping the policy-making process with stronger instruments could result in a more dynamic and sustainable education and training system. The analysis will focus on the two first human capital development (HCD) issues that have direct consequences on the VET system, and which need to be dealt with urgently, as the ETF believes that they are crucial for the socio-economic development of the country and that the current winds of change offer a momentum to be seized in addressing them. While focusing the analysis on these two issues, some recommendations also take into account issues 3 and 4 (e.g. adult education and LLL, the NQF, VNFIL or governance and financing).

Policies for human capital development in Lebanon

Breadcrumb

- Каталог

- Publications & resources

- Publications

- Torino Process reports

- Current: Policies for human capital development in Lebanon

An ETF Torino Process assessment

3. ASSESSMENT OF KEY ISSUES AND POLICY RESPONSES

3.1 Inefficiencies in human capital utilisation due to low levels of job creation and skills mismatch

The problems of youth unemployment and skills mismatch are central to the issues of human capital utilisation in Lebanon. This has been highlighted in all the national Torino Process discussions and reports since 2010, as well as in other strategic documents and studies carried out in recent years.

Limited economic growth, the growing informal sector and the Syrian refugee crisis have progressively led to an increase in unemployment and poverty. Since the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011, it is estimated that around 200 000 Lebanese have been pushed into poverty, and another 250 000–300 000 have become unemployed (World Bank, 2018). In Lebanon's highly fragile context, jobs are critical, not just to reduce poverty and contribute to productivity and growth but also to strengthen social cohesion and avoid radicalisation.

Figure 12: Unemployment Rates by Age Group and Gender, 2018–2019 (%)

Source: CAS (2019)

According the preliminary key findings of the CAS Labour Force and Household Living Conditions Survey (LFHLCS) 2018–2019, the youth (15–24 years) unemployment rate is at its highest since 2012. It rose from 18% in 2012 up to 23.3% in 2018–2019, more than double than the general rate (11.4%), and the likelihood of being unemployed is significantly higher among university graduates (35.7%) of the same age cohort. Moreover, about half of the unemployed young people had been looking for work for more than a year, resulting in feelings of discouragement in relation to jobseeking: the percentage of young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs) is about 22%, and significantly higher among young women (26.8%).

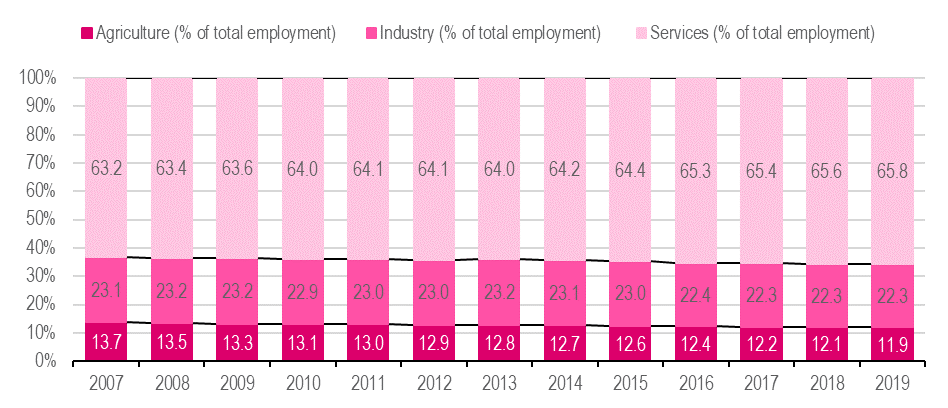

On top of the high and persistent youth unemployment rate, which rises in line with the individual's education level, the limited absorption capacity of the labour market is visible through the presence of skills mismatch. The structure of employment in Lebanon has shifted away from manufacturing and agricultural activities and towards the service sector. McKinsey's Economic Vision Report (2018) estimated that the productive sectors employ only 28% of the labour force, namely agriculture 12%, manufacturing 11%, and hotels and restaurants 5%. According to the LFHLCS 2018–2019, the share of the workforce employed in agriculture has dropped to 4%, with the service sector rate rising to 76%.

Figure 13: Employment by Sector

Source: World Development Indicators (WDI) Database, ILO estimates.

As the labour market is becoming more concentrated in fewer service sector activities with relatively low levels of productivity, the economy cannot generate enough high-skilled jobs to absorb the numbers of university graduates. In fact, among young people in employment, 31.5% were engaged in occupations with qualifications requirements below their level of education (CAS, 2019). Moreover, it was estimated that only 40% of graduates work in jobs that match their qualifications, while 20% are engaged in activities that do not match their educational fields (Dibeh et al., 2016).

Even more important is the low and apparently decreasing level of participation: according to the LFHLCS, less than 50% of the working-age population (15 years and over) were active members of the labour force in 2018–19 (the activity rate was estimated at 54% in 2012[43] Eurostat Database.

). The figures are even lower for women and young people (15–24), with participation rates of, respectively, 29.3% and 39.2%, compared with 70.4% for men. Taking into account the potential labour force, including discouraged from job-search, the survey results also show that 29.4% of the extended youth labour force[44] The “extended youth labour force” is the sum of labour force and potential labour force. The “potential labour force” is defined as all 15+ people who, during the previous 7 days, were neither in employment nor in unemployment, but were: (a) seeking employment but not currently available (unavailable jobseekers); or (b) wanting employment and currently available to work, but did not seek employment (available potential jobseekers, and discouraged potential jobseekers).

were underutilised to various extents in terms of employment (CAS, 2019).

Figure 14: Labour Force Participation Rates, by Age Group and Gender, 2018–2019 (%)

Source: CAS (2019)

Skills deficits and mismatch hinder private-sector growth. A Word Bank enterprise survey released in 2016 estimated that 15% of firms in Lebanon consider a lack of workforce skills as a serious impediment to their operations (World Bank, 2016). A labour market study on electrical technicians in Lebanon, conducted and presented by IECD in 2019[45] Technical education meeting: Results of the Labor Market Study of Electrical Technicians in Lebanon.

, stated that 74% of VET graduates holding a BT (Bac Technique) in électrotechnique chose to go into higher education, either for a TS -Technicien Supérieur- (50%) or University degree (50%), while the remaining graduates opted for civil service employment, especially in the armed forces, taking into account the matter of salary and other benefits.

At the same time, medium-level technical expertise (e.g. skilled workers, technical assistants) is extremely scarce across all occupations in the Lebanese labour market. According to the IECD study (2019), the interviewed enterprises indicated a mismatch between current TS graduate skills and market needs, with over 70% citing a lack of skilled talent and a shortage of technical skills. This is further underlined by an Employers' Survey pilot initiative, carried out by a joint public-private task force and supported by the European Training Foundation (ETF), which reported that 46% of the employers surveyed provided training to their current employees to cover particular skills gaps, namely in maintaining and operating machinery (ETF, 2019a). The lack of organisation and the negative value attributed to these occupations are major obstacles preventing Lebanese people from opting for these professions.

The IECD (2019) labour market study also highlighted the limited presence of women in the VET sector due to gender bias and employers assuming that the working environment is too challenging for women. The latter view reinforces the social perception of gendered roles that leads to steering girls towards non-industrial specialties at school, which further exacerbates the mismatch.

'Mind the Gap: A labour needs assessment for Lebanon', commissioned by UNDP in 2017, covering three sectors (construction, agro-food and ICT) reported skills gaps in relation to semi-skilled labour and stressed the need for further training. Within the agro-food sector specifically, around 40% of employers stated that hiring and keeping qualified employees was an issue for them. Professionals also report that semi-skilled workers' lack of training on quality control techniques and monitoring and evaluation methods is the biggest obstacle they face (Hamade, et al., 2017).

Furthermore, such skills gaps can be ascertained from the sizable inactive population (52%), the high proportion of NEETs (22%) and the underutilised labour force (16.2%, and as much as 30% for the 15–24 age group) which obviously accentuates the deficit of human capital (CAS, 2019).

A youth discussion group organised by the ETF within the framework of the Torino Process 2017 clearly identified the lack of career guidance services and support in the transition from school to work as key issues. The need for better guidance in the choice of education is considered particularly important, as the current system, dictated by traditional values and family influence, frequently guides students towards professions unsuited to their own competences and aspirations. Students often seek advice from their teachers, but most of the staff have insufficient experience or ability to guide students as their knowledge of the world of work is limited. In this context, a clear need was expressed for structured and well-functioning career guidance and career orientation services.

The above factors are also the result of the low social value accorded to VET. Students and parents generally consider that VET qualifications do not add value to their professional and personal development. VET is seen as a last chance for students who fail in general education and who, in most cases, are not even in a position to select a training path appropriate to their capacities and potential because of the lack of career guidance services. Most of those who opt for VET are often seeking to continue in higher education.

VET provision remains disconnected from the demand side of the labour market and does not help in bridging the skills gaps and mismatch. As indicated in previous editions of the Torino Process (ETF, 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016) and in the review of VET governance in Lebanon (ETF, 2016), VET in Lebanon suffers from an absence of vision (being partially covered by the NSF) and strategic planning, as well as being adversely affected by centralised governance and lack of accountability and financial transparency. As a result, in terms of efficiency and effectiveness, it is far from fulfilling its role. Obviously, this impacts negatively on skills provision in the country, and there is a unanimity concerning the factors that contribute to its inadequacy in addressing labour market needs:

Teaching and learning approaches that include outdated curricula, with some exceptions, and lack of mechanisms for curricula development, streamlining and updating;

Limited pre- and in-service teacher training; lack of transparent procedures and criteria for recruitment and performance evaluation. It should be highlighted that more than 80% of staff are contracted on limited terms and so not eligible for professional development;

A highly centralised system that leaves little room for schools to exercise autonomy and innovation (including with regard to planning, monitoring and use of resources);

Work-based learning remains at the piloting stage, although launched more than 20 years ago;

Lack of quality assurance mechanisms. Quality assurance in Lebanon mainly refers to quality control mechanisms such as exams and the accreditation of private providers.

Lack of career guidance and counselling, with some school-based exceptions (i.e. Guidance and Employment Offices – GEOs).

As a result of the change introduced by the DGVTE (as per law nr. 8590 published in 2012), the TS (Technician Supérieur) programme was shortened, from three to two years. This created challenges for the students pursuing different specialties and especially in regulated fields such as nursing, where the Order of Nurses issued a regulation that unless TS students obtain a 'Licence Technique (LT)' or bridge their studies with other academic studies and obtain a Bachelor's degree, they cannot obtain the required licence to work or become a registered nurse. According to the Torino Process national report, the situation is the same in other industrial specialisations (confirmed through interviews with UNDP, IECD, UNICEF and others), with the programme deemed insufficient in duration to equip the students with the proper skills required by labour market.

A recent ILO study on 'Trends in the demand and supply for skills in the agriculture sector' carried out in February 2018, highlights the urgent need for a better trained workforce, especially at the level of technician, and to improve the quality of programmes. The study estimated that agriculture, including own-account and contributing family workers, employs roughly 20–25% of the Lebanese workforce (significantly higher than the usual estimates) and represents the primary source of income for the poorest families (ILO, 218). This represents a skills deficit that the VET system struggles to address.

Furthermore, the concerns over teachers are not only centred on their capacity and development but also on their distribution over schools and students. The increase in the number of schools has not responded to the over-saturation of students in existing schools nor to introducing new specialisations, but to political considerations. In fact, this could explain the low student-teacher ratio in public technical VET, which was as low as 3:43 in 2017/18[46] Figure provided by General Directorate for Vocational and Technical Education, 2019.

.

Above all, the monitoring and evaluation of progress is very difficult to undertake due to the lack of basic official data on enrolment and success or graduate placement rates, whether global, regional or by specialty.

The National Employment Office (NEO) struggles to fulfil its function of intermediation. Another serious and long-lasting problem in Lebanon, in addition to the lack of data, is the limited capacity and resources of the National Employment Office (NEO). The NEO acts by law as a services intermediation agency, but does not have the full human, financial and technical capabilities to adequately perform and develop this role, even though 30 new employees have recently been

recruited. In practice, its role is limited to funding continuing training (an accelerated vocational training programme) for jobseekers and vulnerable groups. At the time of drafting this report, the post of

Director General remains vacant, which may have an even greater influence on the slowdown of its activities. Due to a shortage of resources, other services usually performed by public employment offices, such as registering the unemployed, organising job placements, and providing career information, guidance and counselling are not offered by the NEO. On top of this, the issue of the Office's lack of visibility at the national level limits awareness of its role and therefore jobseekers' ability to access training and general services.

Low learning participation rates for females in general, non-Lebanese in particular and people with disabilities. These sections of the population are at a greater disadvantage in terms of accessing learning opportunities, whether academic or vocational. According to the NRF, the extreme poverty of Syrian households forces them to prioritise the education of boys over girls, preventing girls from continuing their education and exposing them to early marriage. The share of female secondary students enrolled in vocational education, around 12%, is lower than the rate for males, at around 18%[47] UNESCO UIS Database.

.

Figure 15: Share of Female Secondary Vocational Students (as % of Female Secondary Pupils)

Source: UNESCO USI Database

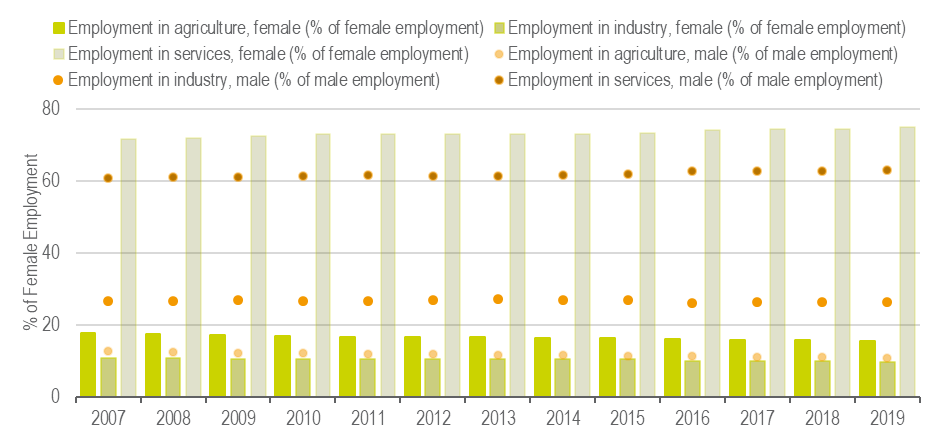

Furthermore, the participation of females is mostly in gender-oriented specialties such as nursing or beauty, with a lower presence in industrial specialties such as électrotechnique, mechanics, etc. This trend is reflected by women's absorption in the labour market, where women's employment in the industrial sector is dramatically lower than men's (9.7% vs. 26.2% in 2019) and decreasing. By contrast, female employment is mainly directed towards the service sector (74.8% for women and 62.9% for men in 2019)[48] World Bank WDI Database, ILO Estimates.

. When it comes to people with disabilities there are no statistics, but the fact that the relevant infrastructure is missing from the majority of schools further hinders their integration into the VET system.

Figure 16: Female Employment by Sector

Source: World Development Indicators (WDI) Database, ILO Estimates

The refugee crisis has exacerbated this situation. In addition to the pressure Syrians refugees have exerted on public infrastructure and services, their presence has increased informality in the labour market, resulting in fewer job opportunities, a reduced quality of job offers and the depression of wages, particularly for low-skilled workers. According to the ILO, the estimated increase in the labour force is 14%, while the World Bank's projections have anticipated an increase of 10 percentage points in unemployment. This is placing additional pressure on already stretched VET services in terms of planning, access and quality. The combined effect of immigration and the emigration of skilled Lebanese graduates, creates at the same time a lack of job opportunities for low-skilled Lebanese graduates and a skills gap for jobs requiring high- and middle-skilled workers that the current VET system is not able to bridge.

An Oxfam skill gap analysis for a number of regions in Lebanon reported a discrepancy in perceiving the impact of the Syrian crisis: while enterprises in Beqaa saw a positive outcome, half of the enterprises in Mount Lebanon saw negative repercussions on the national economy. Among the reported barriers to hiring; skills, legal framework and cultural issues were the most dominant. Enterprises reported a gap between the educational background of the labour force and job market needs. Within the agro-food sector, the report saw a role for employing Syrians in the sector through adequate training (Oxfam, 2017).

3.1.2 Policy responses

As mentioned above, the McKinsey study (2018) highlights six area that should receive priority government support in order to improve growth and employment:

- Agriculture: Lebanon has the largest amount of arable land in the Middle East, and the potential to become the main supplier of high-quality fruit and vegetables for the Levant and Golf countries;

- Industry: Lebanon should capitalise on its creative edge to become a leader in high value-added artistic products, including jewellery, furniture and fashion;

- Tourism: Lebanon should build on its strong natural endowments and strategic location to attract its fair share of inbound tourists (4 million tourists by 2025);

- Knowledge Economy: Lebanon should aspire to become the leading knowledge hub for the Middle East, serving as the region's KPO/BPO[49] KPO: Knowledge Process Outsourcing and BPO: Business Process Outsourcing

destination and the number one tech ecosystem; - Financial Services: Lebanon receives the highest financial deposits relative to its GDP in the world, allowing it to become the financial hub for the Middle East and a gateway for financial transactions globally;

- Diaspora: Lebanon should aspire to leverage its large diaspora to further drive economic growth (McKinsey, 2018).

The National Strategic Framework (NSF) for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) 2018–2022 is certainly the most important development in the sector in recent years. In addition to the fact that the NSF confirms the government's commitment to reform and promoting the VET system, it proposes concrete policy actions for implementation. The main strategic axes are: (i) expanded access and service delivery; (ii) enhanced quality and relevance of VET provision; and (iii) improved VET governance and systems.

A number of reforms were introduced in 2014 in relation to the TS (Technicien Supérieur) and the LT (Licence Technique), and in 2016 for the BP (Brevet Professionnel) and the BT (Bac. Technique)[50] Including the BT in électrotechnique and the new BT in maintenance.

. As part of these reforms, soft skills were incorporated into the curricula, the lack of which having been identified as one of the key impediments to the employability of VET graduates. New VET specialisations have also been introduced in response to labour market demands and industry trends. New areas of expertise include electro-mechanics, sustainable and renewable energy development, IT (smartphone application development), and air conditioning service and repair[51] ETF – Torino Process, 2017.

.

With regard to career guidance and counselling, in 2015 the ETF (EU-GEMM programme) established Guidance and Employment Offices (GEOs) in six public vocational schools, along with dedicated staff trained to facilitate young vocational graduates' transition into the labour market. A Ministerial decree published in May 2015 formalised the position of Guidance Employment Officer within public schools –a strong sign of the government's will to mainstream this function at the national level. A further 12 GEOs are being established in other public schools within the framework of the on-going EU project 'CLOSER' using the GEMM approach. The GEOs have had been introduced into the country's private schools by IECD.

A more recent initiative driven by international organisations, the EU-ProVTE (implemented by GIZ), is a competency-based approach for the modernisation and modularisation of curricula. This reform, operated in the Technical Baccalaureate, if generalised, will ease the transition from school to work, allow recognition of prior learning, and enhance the quality of VET provision in general, and thus its attractiveness.

The UNICEF is working with the DGVTE, within the annual action plans, to modernise the curricula according the competency-based approach and develop qualification framework chart and the description of the learning levels of TVET. This includes the setup of quality standards and production of a self-evaluation manual in a number of technical schools. The UNICEF is also working on the mechanisms for the participation of employers and workers in the various aspects of the TVET system and establishing employers' committees in some sub-disciplinary fields to identify the skills needs. More recently, UNICEF was assigned to work on the development and modernisation of all BT curricula by applying the competency-based approach. It is also expected during 2020 that the EMIS become effective and that starting the school year 2020/2021 all the data regarding the public technical institutes and schools, their students, teachers and administrators will be entered online in the EMIS system.

Finally, since the London Conference in 2016, the Lebanese government has revoked the 'pledge not to work', allowing Syrians to obtain employment in specific sectors. The government has also waived the residency fees for a large number of Syrian refugees. The Brussels Conference emphasised the importance of education for displaced persons, particularly VET, not only in terms of ensuring social inclusion, but also in preparing the Syrian refugees for their subsequent return home post-conflict and their role in Syria's reconstruction (UNICEF-ILO, 2018). Moreover, all the support initiatives in education and training, in job creation and integration into the labour market, encompass both refugees and local communities, especially vulnerable Lebanese groups such as women and young people.

The abovementioned policy responses are highly positive initiatives that have been nationally agreed in the VET sector, and have led to the first such action plans for years. They will certainly contribute to upgrading relevant job skills. However, based on previous experience, some gaps might be observed and underlined as follows.

Most of these policy responses are at the planning and/or piloting phase. The implementation and/or consolidation of pilots has always been an issue in the Lebanese context. The NSF will follow the same pattern if an action plan is not approved and implemented quickly. Precise planning should also be established, including an exit strategy focusing on the sustainability and extension of the models, shared with and owned by policy makers. For instance, in the absence of a nationally agreed framework for work-based learning or a competency-based approach, the piloting of different experimental models could last for ever.

Poor inter-institutional cooperation and the current VET governance setting may hamper the implementation of such structural and extensive reforms. This concern operates at both the policy and practitioner level and calls for new governance arrangements and organised capacity building as well as awareness-raising actions that are not always foreseen in the different policy responses. Inter-institutional cooperation is a challenge particularly between the ministries in charge of education and training, employment, social affairs and the economy, but even inside the different departments and with the private sector.

There is a need for national structured frameworks. Currently there is fragmentation in the VET sector and a lack of endorsed frameworks that would allow more coherence and visibility in terms of reform implementation. This is the case, for instance, in such areas as the recognition of prior learning, work-based learning, partnerships with the private and non-government sectors, the NQF and quality assurance systems, and individuals opting to participate in continuous vocational training (CVT).

The teaching environment remains disconnected from labour market needs, and IPNET is still non-operational. More specifically, most of the contracted teachers in the VET system have academic backgrounds, and a large proportion of those contracted on a yearly basis are recent university and Technicien Supérieur graduates. In addition to contracted permanent staff, part-time teachers are recruited on a short-term basis (sometimes on an hourly basis). While there is clearly merit in the process of using contract teachers in VET institutions as a means to bring practical experience into the classroom, it should be noted that there is no specific legal framework that defines the mechanisms or criteria for recruiting part-time teachers and evaluating their performance. It should be noted that part-time teachers cover the majority of the teaching hours (roughly 90% in 2017/18) (ETF, 2020). One of the reasons for this precarious situation is the fact that the National Training Institution for Technical Education (IPNET), which is in charge of the initial training, graduation and development of VET teachers, has been dormant for many years due to lack of capacity and resources.

A quality assurance system for VET is lacking. Although there is a growing interest in quality assurance, with some isolated initiatives appearing in which quality assurance features significantly. Currently the DGVTE accredits VET providers and programmes through a dedicated commission that checks the implementation of official programmes as well as premises and equipment. Private VET providers require DGVTE accreditation to operate and must follow their official programmes, and students in both public and private VET schools must take the national examinations endorsed by the DGVTE. There is no structured and comprehensive VET management information system, although a dedicated department exists for information/statistics gathering. Data collected on VET participation do not appear to be used for quality assurance purposes (ETF, 2018b).

Addressing the issues of skills gaps and employability in Lebanon requires structural reforms calling for a mix of investments, policy and actions, along with institutional capacity building. Now that a clear strategic framework for VET has been agreed, the following recommendations are proposed to support this initiative and focus on actions related to skills and employability measures, with a special emphasis on proactive actions to combat youth unemployment.

The first set of recommendations (R1.1 to R1.4) covers the need for a multi-level and multi-stakeholder governance as a pre-condition for improving the quality of skills provision as well as their alignment with labour market needs.

As discussed in section 3.1.1, it is widely recognised that centralised governance is one the main factors that hampers the effectiveness of VET in Lebanon. This issue relates to the national, sectoral and local levels and impinges on VET effectiveness and its attractiveness to learners and employers. The current recommendation proposes a comprehensive and coherent approach to addressing this urgent issue by fostering the conditions conducive to a multi-level and multi-stakeholder governance ecosystem that can steer skills development to respond efficiently to the country's socio-economic needs. A possible option could be the experimental governance system that encourages institutional learning by monitoring and identifying joint solutions to common problems through a process of trial and error (Morgan 2018, p. 5; OECD, 2018).

- National: Reactivate and operationalise the Higher Council for VET and foster all kinds of PPP

The operationalisation of the Higher VET Council will be a precondition for the implementation of the reforms and their success. This Council will represent and model partnership with social partners at the national level and will ensure and guarantee the strategic orientations and their implementation. It will also ensure the development of clear mandates for the various stakeholders and encourage shared and well-defined responsibilities and accountability with other institutions beyond public education bodies (ministries, social partners, chambers of commerce, sectoral associations, etc.). This should include all types of public-private partnerships at the national, sectoral or local level. The Council should have a key role in the supervision of the implementation of the NSF Action Plan, once it is validated by the national authorities.

To avoid a repetition of past failures, the composition, legislation, assignments and resources of the Council should be flexible and discussed and agreed with all actors intervening in skills development and utilisation.

- Sectoral: Set up skills councils in priority sectors

Sector Skills Councils (SSCs) are an effective way to involve employers in the practicalities of policy design and ensure that they can play a role in influencing policy. In countries like Lebanon, this may be a way for the private sector to engage in skills planning and policy dialogue, even if no formal role for social partners at the national level exists. The SSCs need to be progressively established as independent employer-led organisations in the economic priority sectors. In addition to their function of skills anticipation, reducing skills gaps and shortages, developing and managing apprenticeship standards etc., the SSCs will seek to build a skills system that is driven by employer demand. The example of the SSC recently established in the construction sector should be expanded to other selected fields.

- Local: Reinforce schools' autonomy and integration with their environment

Without a certain level of human resources and financial autonomy, it will be hard for schools to ensure a high quality of VET provision or improve the attractiveness of the offer to learners and employers. This structural reform implies courageous political decisions and a significant degree of institutional capacity building, as well as developing the appropriate tools for implementation.

To start with, we may envisage developing the concept of vocational excellence in selected VET centres that are strategic for their thematic or geographical scope. This new generation of centres, which have a more comprehensive and inclusive conceptualisation of skills provision, addressing innovation, digitalisation, equity, career guidance, transversal skills, organisational and continuing professional learning, LLL courses, etc., should also have a shared governance setting allowing more management and financial autonomy. This autonomy should go hand in hand with rules for accountability. These examples of good practice would then be progressively extended thematically and geographically.

A second phase would be the setting up of consolidated school networks to optimise teaching and learning resources and improve efficiency. These national networks could open up their cooperative relationships to other international school networks to foster peer learning and future development.

The NRF and other studies have highlighted the problems of VET provision in the country, which have been discussed in section 3.1.1. These issues call for a revision of the uneven distribution of students, teachers and schools, updating of the curricula, further development of teachers with a revision of their status and mode of recruitment, the upgrading of infrastructure and equipment, and the expansion of career guidance services, etc.

The NSF also specifies detailed actions that should be undertaken to improve VET provision. The current recommendations have multiple aspects and focus on the main provision issues that need to be tackled as a matter of priority to achieve better responsiveness to labour market needs.

- Improve the teaching and learning environment for effective VET provision

As discussed in section 3.1.2, the main challenges for the country's VET provision remain the teachers' capacity and curricula modernisation. There is a clear need to undertake a global review of teachers' status, performance and distribution, as well as an analysis of the relevance of existing specialities in order to open up provision to encompass new trades as required by the labour market and stop investing in specialities that don't meet any need. This should include the development, extension and re-distribution of training centres and equipment renewal.

The teaching profession needs to be comprehensively reviewed and reformed. As discussed above, the mode of recruiting teachers and their status need to be radically reassessed, with the objective of increasing their professionalism and opportunities for further development. Professional development within the existing system, with more that 93% of teaching hours delivered by part-timers, would be inefficient and unrealistic.

The IPNET should be reactivated and reorganised to fulfil its mandate, instead of creating new bodies and more layers of bureaucracy that would require further organisational decisions and legislative acts. The IPNET, if reactivated, could play a major role in both curricula reform and teachers' professional development in a sustainable way. Thus, (pre- and in-service) teacher training would be reinforced and integrated as part of the curricula reform.

A major curricula reform and streamlining process is needed to open pathways in the system and enhance VET's attractiveness. Major reform of the curricula requires an enormous effort in terms of time and resources and would need more structural changes in relation to how curricula are monitored and regularly updated, with the involvement of the private sector and building on real labour market needs. Alongside such reform, the streamlining of specialisations in VET is another key issue that needs to be addressed. The streamlining of specialisations should consider for instance, reducing and clustering the BP (Brevet Professionnel) within more general certificates, forming a base for students to progressively increase their specialisation in the BT (Bac. Technique) level. The BT should be structured on specific trades and offer fewer certificates to form the basis for choosing specialisations at the TS level, where a diverse bank of specialities originating from the BT trades is offered. Graduates at TS level would therefore be able to directly enter the labour market. The LT level should offer higher calibre programmes, and more choices should be offered to give VET certification a real value in the labour market. This arrangement calls for the development of clear mechanisms that would lead to decisions about the specialities offered, discontinuing old ones and initiating new ones based on changing labour market needs.

The competency-based approach should be generalised, together with the provision of teacher manuals and guides, and teachers training in this approach through IPNET, if re-activated. This reform may draw on successful pilots such the IECD project on electrical engineering and the GIZ dual system.

- Mainstreaming key competences with a focus on digitalisation and entrepreneurship

While updating the curricula, special attention should be paid to transversal skills as an important need highlighted by labour market surveys. These skills are very much in demand by enterprises, as well as individuals for their personal and professional development, and by society overall. The VET authorities might draw inspiration from the EU 8 Key Competences Framework: Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Translating key competences into learning outcomes is a major step that will guide day-to-day teaching and learning, and pre-define assessment. The Higher Council for VET should ensure that these learning outcomes are consistently specified across curricula. Teachers obviously have a role to play here, notably in the identification of opportunities for learners to develop their specific key competences.

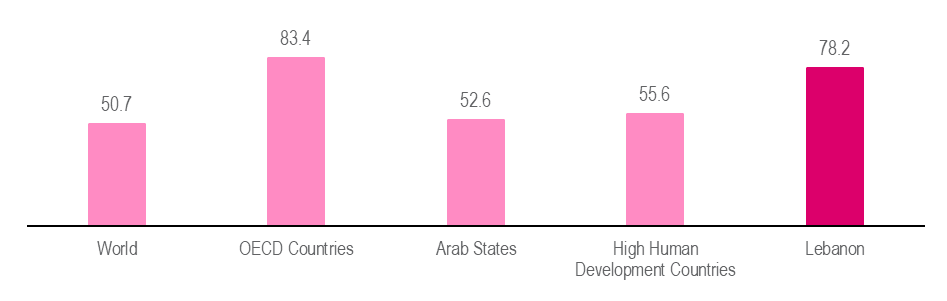

Figure 17: Self-Employed (% of Employment) 2019

Figure 18: Internet Users (% of Population) 2017–2018

Source: ILO, ILOSTAT Database and World Development Indicators Database.

In Lebanon, an initial focus should be on entrepreneurship and digitalisation, in line with the urgent need for economic growth and competitiveness. As discussed above, young people in Lebanon are very entrepreneurial and ready for digitalisation. The Joint Research Centre (JRC) Competence Frameworks for Entrepreneurship (EntreComp) and for Digital Competences (DIGCOMP) can be regarded as examples which can support such work, as they are ready-for-use frameworks and include universal concepts that would fit the Lebanese context.

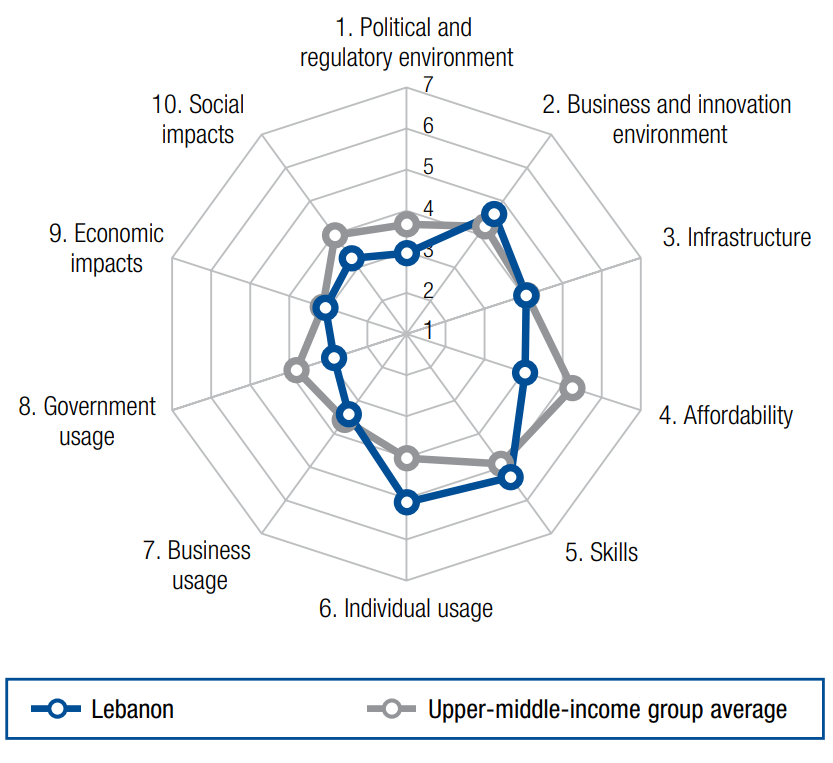

The latest available World Economic Forum's Networked Readiness Index (NRI) ranking, also referred to as Technology Readiness (measuring the propensity for countries to exploit the opportunities offered by ICT), placed Lebanon 88th out of 139 countries in 2016. In spite of its overall poor performance, Lebanon was the second biggest mover from the previous round (2015), gaining 11 places. In terms of the adoption of digital technologies, Lebanon performed well in both individual and business usage. In addition, building on a solid basis in terms of education, skills and knowledge-intensive jobs, Lebanon has many of the factors in place to continue on this positive trajectory.

Figure 19: Networked Readiness Index,2016

Source: World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/

The issues of education, training and employment are currently considered as part of a single process – the school-to-work transition – defined typically as the period between the end of compulsory schooling and the attainment of full-time, stable employment. In addition, the notion of labour market transition in this report includes job-to-job transition, which also needs to be addressed, notably through adult learning from a lifelong perspective and through education and training that further supports individuals' professional mobility throughout the life course.

In the case of Lebanon, this transition is difficult for graduates due to the abovementioned gaps between education and training supply and labour market needs, among other issues. The limited or inadequate policies and institutions currently in place, including labour market measures, career guidance services, work-based learning and apprenticeship, as well as weak institutions such as the NEO, could also be part of the solution and better contribute to easing both the transition from school to work and from work to work, if reorganised and reinforced.

- Review and consolidate a comprehensive and more effective career guidance and counselling system

The current Lebanese career guidance policies and actions are dispersed and isolated. The upstream part of career guidance and counselling, which aims to promote and enhance the profile of the VET system, is covered partly by the MEHE General Education Directorate through its Orientation and Guidance Unit. The DGVTE has developed Career Guidance Offices (GEOs) in some schools, which provide assistance with graduates' placement in the labour market (downstream part of career guidance and counselling). In addition to the GEOs, the school advisory boards follow up on academic and professional progression of students and facilitate their insertion in the job market. The NEO's career guidance services remain very limited.

Given the technological and demographical transformations in Lebanon, which have a direct impact on education and the labour market, a review and expansion of the country's career guidance services is needed for the progressive development of a national lifelong guidance system able to assist both young people and adults in their education, training and employment choices. Strengthening guidance in the school curriculum at an early stage of education (prior to VET), as well within VET, is also recommended to guide students and ease their transition into higher education or work. In the specific case of Lebanon, career guidance services should also be developed for adults and refugees. The private sector is a strong asset in Lebanon and should also participate in the provision of guidance, through private employment services, private education and training providers as well as employers' representations.

To support the above development, the opportunity should be taken by the MEHE to consider establishing a national orientation portal, inspired by successful models elsewhere in the world.

- Reinforce the role of the National Employment Office (NEO) to fully accomplish its role of labour market intermediation

The role of the National Employment Office should be reinforced and improved with regard to its function as a public employment service. In addition to the important part it plays in career guidance, highlighted above, the NEO needs to be strengthened to coordinate and monitor other services supporting employability.

Its mandate should include, as a minimum, the following essential functions: (i) keeping track of registered jobseekers and job offers; (ii) career guidance and counselling; and (iii) delivery of or links to ALMPs. Other functions, such as supervising studies to identify labour market needs, participating in the development of occupational standards led by the private sector, coordinating the future development of an LMIS, etc., could be covered gradually. Job intermediation services for all (e.g. pre-departure information and e-tools for Lebanese emigrants, dedicated services for immigrants, orientation for the most vulnerable groups) could also be progressively included in the NEO mandate (see R.2.8 on emigrants, the diaspora and returnees).

The NEO needs to develop close cooperation with the DGVTEin skills development and employability, as well as with the National Centre for Vocational Training (NCVT) regarding accelerated VET programmes and other public and private short-term training providers and NGOs contributing to skills and employability development. The NEO should further collaborate with other bodies to perform its functions from a customer-oriented perspective – its customers being jobseekers and enterprises.

Finally, once operational again, the NEO needs to be more visible at the national level. To this end, a national awareness-raising campaign about its role and potential should be envisaged to allow for new relations with its ultimate beneficiaries and renovated forms of cooperation with the private sector.

- Regulate and extend work-based learning for more effective and faster transition into employment

Work-based learning (WBL) is the most appropriate way not only to increase the employability of graduates, but also to enhance and consolidate the needed partnerships with the private sector. Well-developed WBL will also solve the perennial challenges of outdated equipment, optimise the use of infrastructure and substantially support VET public financing, as part of the training is hosted by companies.

The initiatives developed so far, such as the dual-system programme or some isolated apprenticeship initiatives, need to be reviewed together with employers' associations and chambers of commerce to better adapt them to the needs and resources of enterprises, which are mainly SMEs. The same goes for the related legislation which should aim to further foster and institutionalise WBL, as well as making it more flexible and adaptable to the needs of enterprises in general and to smaller concerns in particular.

Apprenticeships should be developed in the first stage as an important WBL mode for special target populations such as NEETs. However, the absorption capacity of companies (together with their size and potential for growth) should be considered in the planning of such programmes. Traineeships are more often developed by schools, but need to be structured and organised. This includes careful selection of appropriate companies, and managing the number, distribution and preparation of students, as well as the follow-up by teachers.

In addition to the above, the development of WBL implies clear roles for school managers and teachers with regard to the promotion and implementation of this effective mode of training. Enhancing the autonomy of schools (see R 1.1.c) will ease this process.

The efforts to bridge the gap of skills mismatch and improve employability should consider the completion and institutionalisation of previous endeavours to develop frameworks, such us Quality Assurance (QA), the National Qualification Framework (NQF) or the validation of non-formal and informal learning (VNFIL). These frameworks, if implemented, would also extend benefits to vulnerable populations such us migrants, young people, NEETS, women, and those with low educational attainment.

- Develop a quality assurance framework

Developing a quality assurance framework first of all supposes that there is an official definition of VET quality, which is missing currently. The VET quality assurance arrangements should be a systematic set of procedures and processes based on principles of accountability, transparency and effectiveness. These will ensure that the behaviours and activities of all actors engaged in VET (the government, VET providers, etc.) whether in the public or the private sector, are congruent with the criteria, standards and norms that have been established to achieve clear and purposeful goals and outcomes through the work of the VET sector[52] ETF QA note 2017. The ETF defines quality assurance in VET as 'the measures established to verify that processes and procedures are in place which aim to ensure the quality of VET. The measures relate to quality standards with underlying principles, criteria and indicators'.

. Policy makers should draw on the current ad hoc initiatives in which quality assurance features significantly across the policy cycle, from planning through to implementation, to develop a systemic and systematic approach. This includes such practices as ad hoc cooperation with employers, chambers of commerce and associations of industrialists on skills development and assessment, working on the accreditation of private providers, developing donors' initiatives on curricula reform, defining learning outcomes, promoting work-based learning, and overseeing teacher training.

- Complete and formalise the National Qualifications Framework

Qualifications offered by the Lebanese education system, including VET, vary greatly between public and private providers delivering national and international certificates. As mentioned in the NSF, the update of the qualifications system will prevent further development of the curricula using outdated ways, sometimes without even specifying the purpose of the diploma, the reason for its existence and the system used for the application of the teaching and learning process etc. In order to make the qualifications system more transparent, in 2012–2015 the MEHE, with the support of the ETF, implemented a project to develop a Lebanese National Qualifications Framework (LNQF). A matrix was developed and agreed, comprising eight levels with corresponding descriptors, but no decision on legal and institutional arrangements was made. It would be more efficient to draw on this project, as well as on work recently carried out for VET, to develop an overall national qualification framework. The NQF should be also referenced against the EU framework to promote academic and professional mobility for citizens across borders. A national qualification committee should be set up to steer this collaborative action

- Set up a system for the validation of the non-formal and informal learning

The quality assurance and the national qualifications frameworks would ease the establishment, in the short to mid-term, of a system for the validation of non-formal and informal learning (VNFIL). If, in addition, the provision of adult education from a lifelong learning perspective (see R.2.10 is reinforced, this would help to bridge skills gaps and fill vacancies by equipping people with the required skills. Given the demographic transformations in the country, this initiative would benefit not only the Lebanese but also the refugees, by helping them to participate in the socio-economic development of Lebanon as well ensuring they are better prepared for rebuilding Syria on returning home post-conflict.

3.2 Limited institutional capacity and resources for policy reform and ownership leading to inequity and the disconnection of VET from labour market requirements

Policy reform in general, and strategic planning and evidence-based programming in particular, have always been problematic in Lebanon, and many isolated and unsuccessful attempts have been made in this area. The reasons for this are many and do not only relate to the shortage of data. The first condition for sound policy reform is to have a clear vision for human development from which a coherent and agreed strategy and action plans for VET system reform should emerge. The vision, strategy and action plans should be set up in concert with the main actors in the field of human capital and skills development, such as social partners, other ministries, civil society and local authorities, as well as private VET providers. Currently the conditions for effectively planning, implementing and monitoring VET policy reforms are not present.

The lack of data and the absence of an LMIS exacerbate the policy-making process. Labour Force Surveys have never been systematically carried out in Lebanon. As previously mentioned, at the time the current report was being finalised, the CAS made available the preliminary key findings from its first Labour Force and Households' Living Conditions Survey carried out in 2018–2019. It not yet clear if this will be a regular exercise, as is the case worldwide. Consequently, no LMIS is in place to track labour market demand and supply over time, which prevents policy making from properly addressing the country's skills shortages and mismatch issues.

In 2018, in the framework of the Youth Employment in the Mediterranean (YEM) Project, supported by the European Union and UNESCO, conducted a review on establishing an LMIS in Lebanon. The report covered assessments of labour market studies' methodologies, data collection, and interest in an LMIS in Lebanon. The review concluded (and confirmed) that there is a vacuum in labour market information that is currently partially filled by the national employment office and independent employment programmes carried out by NGOs or the private sector (UNESCO, 2018).

Together with governance and institutional arrangements, financing presents a long-lasting challenge that hampers skills policy reform and development in the country. While it is difficult to obtain official information on financing, it is recognised, as mentioned in section 1.2, that the education sector constitutes one of the main contributors to Lebanon's GDP and that public IVET is financed mainly through the general public budget. The DGVTE budget averages annually about 0.5% of the total government budget and less than 10% of the total education budget, with salaries constituting more than 94% of it. In addition to the insufficient budget, due to the non-diversification of financing mechanisms there are other problems in this area, such as the lack of costing, the allocation of budgets to VET providers without any performance conditions, and the centralised nature of financial management along with its lack of transparency (ETF, 2016). Moreover, the country's limited human, material and financial resources mean that institutional and policy development is constantly at risk.

There is a lack of policy coherence in the short training offer for jobseekers, employees, refugees and vulnerable populations, in particular on those courses offered to Syrians and vulnerable Lebanese as a result of the Syrian crisis. This phenomenon has created: (i) a fragmentation of the system due to the high number of short training courses often provided by NGOs and other private providers; (ii) a lack of overview at the sectorial and geographical level, with courses offered sometimes in the same area and on the same topic; and (iii) a decrease of participation rates in formal VET because shorter, funded courses are seen as a quicker way to access the labour market. Given the importance of continuing training for bridging the skills mismatch and increasing the employability of jobseekers, a global review of this training offer is needed. This calls for more policy coherence and a consolidated framework, notably through a clear strategy of adult learning from a lifelong perspective.

The potential of emigrants, the diaspora and returnees are untapped, as their role and human potential is underestimated by the national authorities. The concept of 'brain gain', complementary to the well-known 'brain drain', relies on the assumption that the outflow of skilled labour can generate medium or long-term beneficial effects in the country of origin in various forms. Examples include return migration that could imply a transfer of knowledge, skills and technologies, or international remittances providing liquidity to alleviate poverty and increase investments. The overall net impact of skilled labour emigration (brain drain vs. brain gain) would depend on Lebanon's responses and adaptation processes at the institutional and policy levels.

Figure 20: Migrant Remittances Inflow

Source: The World Bank Migration and Remittances Data as of Oct. 2019.

Regional disparities mean that all the above challenges are even more prominent in rural and remote areas and endanger social cohesion. Regional disparities in terms of economic opportunities are unambiguous, with most of the poor living in lagging regions outside of Beirut and Mount Lebanon. Poverty rates in the Beqaa, North, and South Lebanon regions are well above the national average and around twice as high as in Mount Lebanon and Beirut (CAS and World Bank, 2015). This is linked closely with labour market outcomes, with trailing regions having much lower labour force participation, higher unemployment, and significantly higher reliance on self-employment (World Bank, 2018).

Figure 21: Unemployment Rates by Region

Source: CAS (2019)

VET provision in rural areas shows the same deficits and inequities, especially for women, young people and refugees. Indeed, the geographical distribution of VET schools looks to be quite arbitrary and doesn't appear to follow a master plan or take into account socio-economic needs. The establishment of new schools seems random and is often based on political and sectarian criteria rather than on market needs at the local level. A more coherent distribution of VET schools is often advocated in the Torino Process and other analyses of the system, both in terms of specialities and geographically.

For instance, in 2017, a skills gap analysis validation was implemented by Oxfam in the Mount Lebanon region for the food, construction, gardening and manufacturing sectors (Oxfam, 2017). The food-related sector had the largest number of full-time employees, with the majority being women. Most employers stated that they need VET graduates because they don't have the capacity to train uneducated workers. At the same time they are looking for employees ready to work long hours for low wages. Enterprises expressed a willingness for partnerships with vocational training programmes in many areas (Hamade et al., 2017).

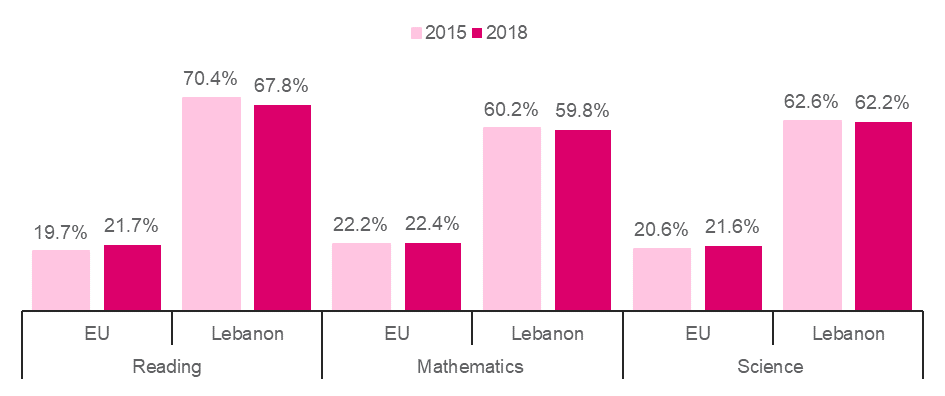

The results of the International Student Assessment (PISA) 2015 and 2018 highlight problems in the quality of basic education. Although Lebanon slightly improved its results from 2015 to 2018 (OECD, 2019), the low level of achievement in reading, mathematics and science is worrying. This low performance will obviously follow these pupils throughout their life, including in the VET system and/or the workplace, depending on their future stream.

Figure 22: PISA Underachievement (% aged 15)

Source: OECD (2019).

The above-mentioned issues are all interrelated, which intensifies the challenge facing policy makers in addressing them in an integrated and coherent manner. Previous attempts to address them separately, without a unified vision and strategy, proved to be ineffectual.

3.2.2 Policy responses

As mentioned above, with the support of international organisations and in consultation with the main VET actors in the country, the country has developed a National Strategic Framework 2018–2022 (NSF). This framework stipulates an inclusive VET sector, with a tripartite governance system, that provides skills for work and life. It should also have a permeable structure with pathways throughout the education system, and be attractive to young people and enterprises. One concrete result of this strategic initiative is the resumption of the Higher Council for VET, which organised its first meeting in 2019 after years of dormancy.

An action plan for the NSF has been prepared and is currently undergoing validation. The plan, once approved, will bring together the relevant national authorities for the implementation phase, which will hopefully cover most of the recommendations and systems gaps highlighted in this assessment.

It is also important to note that the ILO, together with the CAS, recently finalised the Labour Force Survey (LFS), funded by the European Union. This initiative is viewed as a major achievement in the move towards skills demand identification and as a basis for planning future interventions in the area of employability. The LFS would be also used for designing a national employment policy. Preliminary results have made available but the full report has not yet been published, and is awaiting clearance by the Prime Minister.

In terms of the influx of refugees into the country, substantial programmes funded by international organisations and led by the MEHE, such as the EU Regional Trust Fund (EUTF) in Response to the Syrian Crisis (the 'Madad Fund'), are attempting to address the issue, notably by ensuring that Syrian as well as Lebanese youth have better access to VET. While the crisis was initially managed primarily from the humanitarian perspective, the government has now made efforts to centralise and coordinate a number of measures to tackle issues related to the labour market and education and training in particular. The leading principle underpinning all the actions is that they should address the needs of the Lebanese communities in parallel with the needs of the refugees, while it is further envisaged that the support given should enable the Syrians to acquire the skills that will be needed once they can return to their country. In addition, within the framework of this initiative, in December 2019 the Madad Board approved the action document 'EUTF support to economic development and social stability in Lebanon'. This action, – entitled VET4all – recognised job-related competences for Syrian refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and vulnerable Lebanese in response to the Syrian crisis. It will aim to upscale the experience of the current programme – ProVTE – in designing and delivering modular competence-based training (CBT).

Another positive change is the new management of DGVTE, which seems to be more open and responsive to the needs of a multilevel governance structure and strategic and documented planning. The current momentum around the National Strategic Framework and the regular Torino Process VET review could support the DGVTE management to plan and activate the NSF.

Shortcomings and policy gaps

A national vision on human capital development is still lacking. One of the reasons related to the absence of a national HCD vision is the challenging tripartite approach and insufficient inter-institutional cooperation in Lebanon. Establishing such cooperation would ensure that the vision is coherent with other national strategic socio-economic policies. Without this vision, the VET strategies and actions, and any policy planning, will remain only partially equipped to address the huge skills challenges in the country. Such a vision would make the NSF more effective, especially in terms of ensuring the permeability of VET with general and higher education, and further highlighting the importance of LLL, social inclusion and economic competitiveness. In addition, the NSF and its aims would be strengthened by securing the agreement of the major stakeholders concerned.

Although positive, the NSF and related action plan initiatives are mostly donor-driven, which raises the issue of possible non-appropriation and lack of ownership by national policy makers, as has been the case in many donor-driven programmes in the past. Considering the complexity of these reforms, the high number of stakeholders that will (should) be involved and their structural and complex nature, the implementation phase calls for sound planning and the practical involvement of policy makers and beneficiaries, including end-users, which is not always easy to achieve in the Lebanese context.

The initiatives requiring legislative reforms risk being delayed in the current political vacuum. Lebanon's sectarian political system has always been an obstacle for legislative reforms. Initiatives such as the NQF, quality assurance, key competence curricula, etc., although technically very advanced, have been blocked at the legislative stage for years. This risk is even higher in the context of the recent political turbulence and unrest.

The issue of missing labour market data will not be completely resolved by a one-off Labour Force Survey. As mentioned above, this initiative is also donor-driven and its chances of achieving sustainability and ownership within the country are still unclear. The LFS is indeed costly, but it is also inevitable and needs to be fully integrated into the country's systems and repeated regularly. Besides, the LFS alone will not be sufficient to inform and document skills anticipation and matching or build a prospective LMIS.

A multilevel governance system builds on trust and dialogue with partners, which are still insufficiently established in Lebanon. More and clearer signals, showing the good will of VET authorities towards reform, need to be sent to skills actors and partners, especially the private sector and students. This is a challenging action that would need substantive support in awareness creation and capacity building.

The VET policy responses do not meet the huge social and inclusion demands triggered notably by the recent demographic transformations. Meeting the demands of social inclusion means ensuring access to VET for vulnerable and marginalised groups, NEETs, rural populations, and especially girls and young people operating in the informal sector, as well as upskilling workers through continuous training.

3.2.3 Recommendations

This second set of recommendations focuses on the amelioration of institutional capacity and resources to better face the different challenges of policy implementation and ensure greater ownership and sustainability of reforms. The policy directions should be translated into executable, measurable and accountable actions.

Success relies on the strategy clarifying the position of each stakeholder in the overall system and illustrating the different kinds of relationships and reporting lines. Whenever several stakeholders are assigned identical responsibilities and tasks, be it in the strategy or in the action plans, then a lead should be identified and clearly assigned. This creates the conditions for responsibility and accountability to flourish.

The momentum created around the national VET strategic framework and the hoped-for political transition could present an opportunity to put the agreed measures into action, avoiding past mistakes and political constraints. The NSF defines the mission of VET reform as creating a system that is 'tripartite-led, fit for purpose and inclusive' and which will 'provide competencies and life skills to meet the skills demand in the labour market, forming part of a larger education system with multiple pathways to encourage lifelong learning'.

R.2.5 Create the conditions to gradually establish a national labour market information system (LMIS)

This recommendation should in fact serve as a basis for all the others because sound decision making should be well documented and evidence-based. Based on the available studies and consultations with the relevant actors, the Torino Process national report emphasised the need to develop a labour market information system. The report also recommended investment to enhance the capacities of the business sector in an effort to improve its contribution to the establishment of an efficient LMIS aligned with labour-market demand.

A reliable and coherent LMIS system has to rely on the institutional arrangements and procedures that coordinate the collection, processing, storage, retrieval and dissemination of labour market information. The term 'information system' not only refers to information technology systems, but to a comprehensive set of institutional arrangements, technology platforms, datasets and information flows, and the way these are combined to provide information to those requiring it (ETF, 2017a). The Labour Force Survey should be an integral part of the LMIS.

This is obviously a challenging endeavour in the current country context. As there is no general blueprint for a single and effective LMIS, a first step would be to define the aim, scope (education, employment, economy, etc.) and level (national, regional, sectoral) of the most-needed analysis. The VET system is clearly an important part of an LMIS and should build its own information system. The main purpose of data collection (quantitative and qualitative) and analysis should be to provide labour market actors with the necessary information to bridge skills mismatches, but it also needs to support career guidance services that will lead to better occupation choices, as well as adapting ALMPs to be more efficient and able to anticipate and plan changes in skill requirements for specific sectors. A reliable LMIS is essential for good career guidance services and in providing information for pupils, students, employers and the public in general. As with the other reform initiatives, this requires a substantial reinforcement of capacity building and a high level of cooperation with the private sector, CAS, the Ministry of Labour and the NEO, among others.

R.2.6 Diversifying the financial mechanisms to address policy priorities, further engage the private sector and ensure greater sustainability

As discussed in section 3.2.1, the financial resources of the VET sector do not cover its needs as they are delivered mainly through the state-budget and are insufficiently diversified. A shared governance approach to addressing policy priorities should also cover VET financing and the diversification of its sources. The ETF recommends initiating this reform through a review of the current budget formation and allocation process and its efficiency in providing the right skills (see ETF, 2018a). This should lead to the following actions.

- Develop an agreed costing methodology to ensure accurate and sustainable budget planning and execution. Simulating the financial implications of policy options can check whether choices are realistic and sustainable over time. It is important that the current strategy includes estimations of the costs related to the outcomes and to the activities in the ongoing action plan. This will give better predictability in terms of the resources needed over the implementation period. Using the cost variable as a decision factor in a VET strategy supposes the availability of data, not only on financial issues but for the VET system as a whole.

- Diversify the sources of funds and increase the share of non-state resources to implement the current ambitious strategy and engage the private sector in practical ways. The diversification of financing sources assumes an economically fair cost-benefit approach, ensuring that those who benefit from public policies also contribute to them. This contribution, or funding formula and conditions, could take many forms, such as a training levy and related incentives, income generation by schools, tuition, etc. In the Lebanese context, one concrete and quick way to increase VET resources could be the extension of work-based learning (see R.1.3c). This extension could cover, in a first stage, the priority occupations needed for national economic development and job creation.

- Move towards a more performance-oriented approach to resource allocation. Currently, the budget is determined by a simple percentage increase (or decrease) on the previous year's budget without taking into account the performance of providers or the achievement of VET policy objectives (the historic incremental approach). Policy makers should consider establishing basic criteria for the allocation of funds based on performance and policy priorities (i.e. enrolment, graduation, placement, continuing training, work-based learning, social inclusion, etc.).

- Give more financial autonomy to VET schools so that they can respond to local labour market needs and promote innovation. This should go hand in hand with the reinforcement of schools' management capacity and revisiting the accountability rules, based on a defined priorities mechanism and agreed objectives (see also R1.1c). This autonomy will also reinforce the financial diversification of resources, as schools will be able to generate income, to the extent possible, through the provision of goods and services.

Finally, policy planning should take into account the various sources of funds, both public and private (including private VET providers and donors' contributions), in order to bridge the current gap between strategies and actual achievements, while ensuring greater visibility and transparency and making the policy more credible.

R.2.7 Ensure a progressive transition from donor- to country-led VET planning, implementation and monitoring

This is a generic and important recommendation for policy makers to ensure greater relevance, coherence and sustainability in the field of skills development in Lebanon. Policy makers need to gradually take the helm in terms of VET planning, implementation and monitoring. This will require organisational and capacity review and reinforcement. The case of Project Management Unit (PMU) managing the EU Regional Trust Fund (Madad Fund) in the MEHE could be considered as a good example and a first step towards regaining control of policy supervision.

- Full ownership would require a broader base of stakeholder commitment and collaboration. Horizontal coordination across ministries in particular merits development, namely with the Ministries in charge of labour, economic development, social affairs, etc. Cooperation and coordination with private sector players should be both horizontal across sectors and vertical (including the national, intermediate and local levels). This would allow a renewed multi-level governance of human capital development policies, while giving more space, power and capacity to national actors for decision making throughout the overall policy cycle.

- Policy uptake and ownership means also having the financial capacity and autonomy to support reforms. This requires urgent interventions to increase the share of non-state resources by diversifying the sources of funding (see R.2.6) and providing more autonomy to schools (see R.1.1c)

- A monitoring and evaluation system needs to be established to assess the progress of policy implementation. Building and institutionalising a shared and impacted-oriented monitoring and evaluation framework will not only support evidence-based policy making and reinforce policy making per se, but it will also foster the engagement of actors in the policy cycle and increase their responsibility and accountability within a more transparent reform process.

Lebanon is still in need of extensive support from the international community as a consequence of its limited capacity and resources, as well as its substantial deficits in the area of human capital development and use. The current and upcoming support should clearly anticipate the need for appropriation activities and an exit strategy in order that the outcomes can be sustained. Otherwise, there is a risk that the situation could remain unchanged.

R.2.8 Give more policy attention to Lebanese emigrants, including those in the pre-departure stage, the diaspora and returnees

Emigration is a key aspect of Lebanese history and its present socio-economic situation. Further investment should be dedicated to supporting Lebanese emigrants, including those in the pre-departure stage, the diaspora and returnees. Investment, in particular in promoting the employability of emigrants, can positively impact on the development of both receiving countries and Lebanon, yielding economic returns that could potentially be much higher than the initial investment (ETF, 2017b). Incentives and new schemes for remittances could also be created to redirect such sums away from consumption and towards productive activities that could generate jobs and increase the amount of migrant inward investment, which fell from 18% of GDP in 2010 to 12.5% in 2019[53] World Bank Migration and Remittances Database, Oct. 2019 estimates based on IMF data and OECD GDP estimates, 2019.

.

This calls for more engagement of the international private sector, in particular the Lebanese diaspora, to generate social, cultural and economic benefits in Lebanon, which could include activities such as:

- Mapping the profile of Lebanese emigrants (including returnees);

- Exchange programmes for Lebanese nationals studying and working abroad to attract them back to the country (even temporarily);

- Business management and entrepreneurship training for returnees;

- Micro-credit schemes;

- Remittances schemes for investing in productive activities in Lebanon, including components such as skills development[54] Recommendations of Migrant Support Measures from an Employment and Skills Perspective (MISMES) (ETF, 2017b).

.

R.2.9 The potential of the private sector should be more effectively tapped and anchored in policy making and reform of the skills system

The private sector is a strong asset in Lebanon that should be given more space in national policy making and socio-economic development and monitoring. In the area of human capital development and utilisation, the private sector could play a more prominent role in improving employability and reducing skills gaps and skills mismatch at the national and international (see R.2.8) levels, if fully involved in the policy cycle, as proposed by almost all the recommendations of this analysis. This involvement could range from contributing to VET governance and financing to the amelioration and reinforcement of skills provision and monitoring.

R.2.10. Reinforce adult education and training from a lifelong learning perspective to improve employability, close mismatch gaps and ensure greater equity

The ETF recommends that the authorities develop a lifelong learning (LLL) policy aimed at improving knowledge, skills and/or qualifications for personal, social and/or professional reasons. Lifelong learning is a conceptual and policy approach that makes the most of formal, non-formal and informal learning on a continuous basis throughout people's life course. The conceptual development of LLL encompasses an adult learning strategy which should fully involve the education sector, including both public and private training providers, as well as civil society and the MoL/NEO. It should target jobseekers with the aim of closing at least part of the current skills gap, while also focusing on marginal and displaced populations to optimise the use and development of human capital. A lifelong learning perspective and continuing training actions can also be used as leverage to attract inactive populations, including NEETs, and ease their transition into the labour market